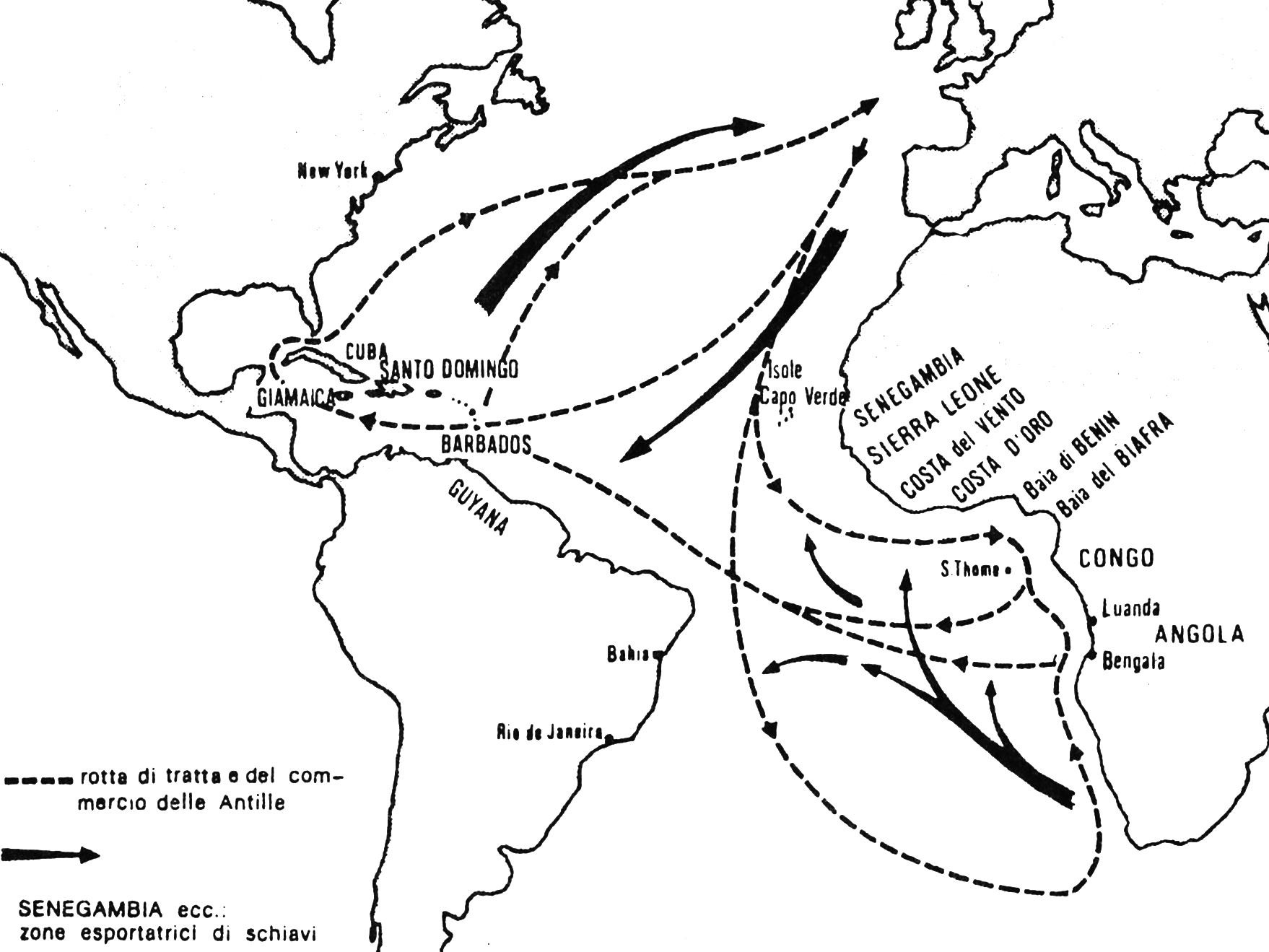

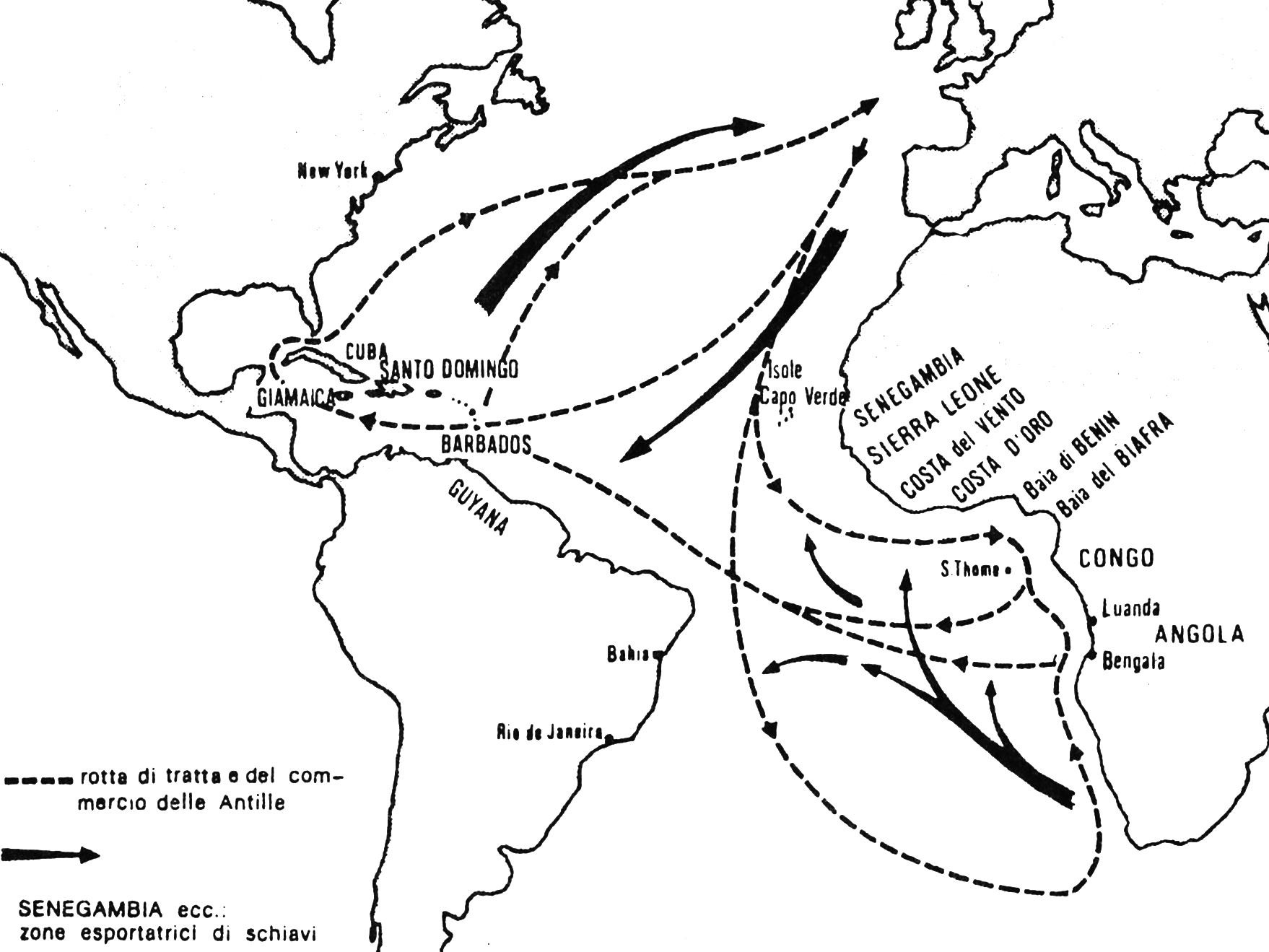

Slave Trade and Commerce in the Antilles in the 18th Century

(R.Anstey, The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1810, London 1975)

|

||

|

Monographs on Latin America 1959-1995 |

|

– A. The Causes of Latin America’s Backwardness (from Il Programma Comunista, Nos.14-15, 1959, now in Comunismo No.38, 1995) – B. The Formation of Nation-States in Latin America (Comunismo, Nos.15-16, 1984) – C. Revolution and Peasant Question in Mexico (Comunismo, No.39, 1995 and No.41, 1996) – D. Aspects and Limitations of the Capitalist Economic System in Latin America (Comunismo, No. 19, 1985) |

Preface from 1995

The party has undertaken a study on Mexico with the aim of bringing into focus the causes that determine the crisis that the country is currently experiencing and the economic and social environment in which it is taking place.

The recent peasant revolts in Chiapas highlights the theme of an agrarian question of considerable importance.

But also, the growing impoverishment of the proletariat is certainly a harbinger of strong social tensions that are likely to manifest themselves soon in a modern, industrialised country with almost 90 million inhabitants, bordering the capitalist giant USA and, in a certain sense, intertwined with its economy. It is however also oppressed by the crises that characterise the underdevelopment of neighbouring Central and South America. A country that acts as a buffer, not only geographically, and may perhaps represent the key to a revolutionary crisis that will set the entire American continent ablaze in the future.

Although Mexico’s history has particular features that characterise it and clearly differentiate it from that of other Latin American countries, we deem it appropriate to present a general overview of the fundamental themes affecting this geographical area, as provided by the following article that appeared in our press, in ‘Programma’, issues 14 and 15 of 1959. This serves as a preface to the presentation of our work on Mexico, which we intend to present at future party meetings and in upcoming issues of the journal.

* * *

Since the end of the Second World War, a profound economic, social, and political upheaval has been underway in Latin America. The social turmoil caused by conflict throughout the colonised region could not spare the Latin American subcontinent, which, despite having broken its ancient colonial ties over a century ago, remained and still remains a quasi-colony of imperialist finance capital.

Much has been written about the awakening of Latin America, and very often there is talk of revolution, when the discussion does not even discuss the ‘feudal structures’ that would still be present in the social fabric. In order to determine the actual significance of events in Latin America, their nature and social outcome, it is necessary to understand the broad outlines of the historical evolution of the subcontinent. Faithful to determinism, we know that nothing happens in the present that is not conditioned by events often located in the distant past. Spontaneous generation, proven false in biology, is also completely absent in historical evolution. This truth is particularly striking when studying countries that have lagged behind in the march of progress. In them the structures of society remain crystallised and change with exasperating slowness, because the influences of past upheavals persist stubbornly and the ‘new’ cannot be regenerated by a pure act of collective will.

In Latin American society reigns an obstacle that seems as immovable and eternal as the gigantic ruins of ancient pre-Columbian monuments: large land ownership. The last century of Latin American history, which coincides with the history of the independence of the twenty republics of the subcontinent, can be summed up, without fear of oversimplification, in one sentence: the obstinate struggle against the land-owning oligarchies, holders of the monopoly of wealth and political power. Over the decades, the struggle took on different aspects as the various social strata generated by historical evolution joined the enemy camp of the landed aristocracy: the urban and intellectual petty bourgeoisie (the famous clases medias), industrial and commercial entrepreneurs and, from the end of the last century, the first nuclei of the socialist wage-earning proletariat. The struggle for and against the landed aristocracy represented, in the troubled history of the Latin American republics, dense with bitter political competition, revolts, coups d’état, bloody civil wars, the clash between conservation and progress, between reaction and renewal (attributing, of course, the exact meaning to these terms, which are all part of the analysis of a structure tending towards capitalism).

Such a phenomenon is not unique in the history of capitalism. Indeed, all the anti-feudal revolutions in Europe, including those in England and France, went through a period that saw the rivalry between the two great branches of the sections of the bourgeois ruling class flare up: landowners and industrial entrepreneurs. In each case, the resistance of the landowners was broken, and agriculture became the docile vassal of financial and industrial capital. The works of the classical bourgeois economists, especially in the Ricardian school, which recognises the right of the class of industrial entrepreneurs to social primacy, remain the doctrinal echo of this conflict.

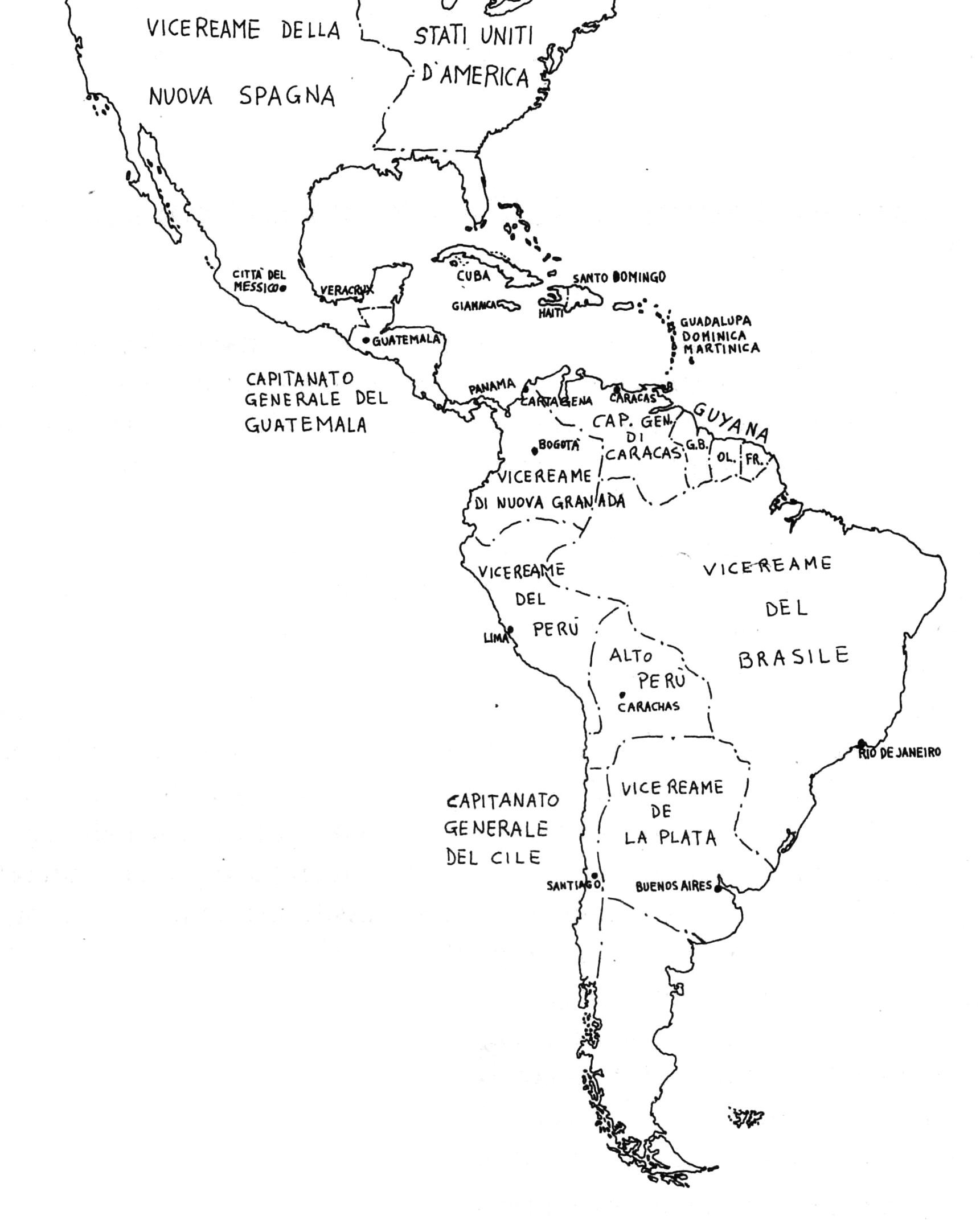

It is necessary then to explain the causes of the exceptional capacity for resistance of Latin American landed property. First of all, we must resist the easy temptation to see it as a feudal remnant. True feudalism in the colonial empire that the Spanish and Portuguese created for themselves in the Americas at the beginning of the 16th century never existed, if only for the fact that feudalism was in decline everywhere at the time of the great geographical discoveries and the introduction of the colonial regime. But the specific reason for the failed transplant into the colonies of the feudal structures still in vogue in the metropolises is to be found in the policy of the absolute Monarchies which, having come into possession of vast colonial empires, were careful not to create in the overseas countries a duplicate of the hereditary landed nobility, which they tenaciously fought in the metropolises. On the contrary, Spain and Portugal imposed on the colonies a bloated state bureaucracy, which, from the centre to the periphery, meticulously controlled every activity of the colonists transplanted to overseas lands.

The encomienda, that is, the concession of large plots of land that the sovereign granted to ‘Creole’ colonists, only repeated, and only in appearance, the feudal system. The encomendero was the absolute lord, not only of the land, but of the Indian population and the Negro slaves who worked like animals on the plantations. However, the right of hereditary transmission of possession, which in European feudalism had as an effect the formation of a hereditary nobility, was not recognised for the fazendiero and the estanciero. In fact, the Crown reserved the right to revoke the concession of the encomienda after a predetermined period, which lasted up to a maximum of two generations.

This infringement of property rights and the exorbitant taxation practiced by the mobilisation of colonial officials of the Crown, who, despite the bonds of race and language, treated the Creole aristocracy with arrogance, the prohibition of trade with any ports other than those of the metropolis, were bound, in the long run, to sow the seeds of revolt among even the ruthless exploiters and oppressors of the indigenous workers and Negro slaves. Thus, it came to pass that a class that was ultra-reactionary towards local workers, to whom every attempt at revolt was paid for with fierce repression, became revolutionary towards the metropolitan colonial power. And when the moment came, it did not hesitate to launch itself into a true civil war, demanding arms against the imperial armies that nevertheless spoke the same language.

Such is, in our opinion, the essential characteristic of the national revolution in Latin America. In Europe, especially the revolution against monarchical absolutism, it meant the liberation of serfs, even if the old serfdom was later replaced by the new modern slavery of wage labour. In Latin America, on the other hand, the class of planters, owners of huge agricultural enterprises and armies of black slaves, rose up against Spanish and Portuguese absolutism primarily to free themselves from the bureaucratic control of the Crown and to be able to possess totally and uncontestedly their own goods, in order to perpetuate slave labour and racial domination for their exclusive benefit.

Having directly and actively participated in the anti-colonial revolution explains the unshakability of positions that the Creole landed aristocracy assumed in the social structure that emerged within the framework of the new Latin American republic. The Latin American national revolution, which followed shortly after the revolt of the thirteen North American colonies against England, was contemporaneous with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, taking place in the period from 1808 to 1823, with varying degrees of success. The anti-Spanish rebels became enthusiastic about libertarian and democratic ideals and wanted to champion the principles of Rousseau, Voltaire, Montesquieu. But in the end, they were powerless to remove the obstacle of large landed and slave property. On the contrary, it was the Creole landed aristocracy that reaped all the fruits of the great upheaval. And this happens, we repeat, because the democratic and progressive camp, which nonetheless had legendary leaders such as Miranda, Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, was unable to effectively fight against a class that participated in the revolt against Spain and Portugal. And this represented a real tragedy for Latin America. If the revolution could not ensure the continuation of the political unity of the sub-continentals, this was precisely because of the tenacious and bitter opposition of the class of landowners, which caused the generous plans for a continental federation, supported by Simón Bolívar, to fail, and thus condemned to fragmentation and economic impotence the immense territory of the defunct Hispano-Portuguese empire.

Latin America possesses great mineral and agricultural resources, but the exploitation of natural resources is severely hampered by communication difficulties. Extending over a large part of the territory within the torrid zone, the subcontinent has physical characteristics that condemn vast regions to isolation: the endless blanket of virgin forest covering the territories crossed by the Equator, the arid tropical deserts, the savannahs, the steppes, the water regime of gigantic river arteries, which often flood vast regions. And, from one end to the other, the formidable barrier of the Andes and the Rocky Mountains, which enclose between their mountain ranges vast plateaus rising to 3,000-4,000 metres. It is understandable how, in a region that nature has shaped in such a way as to make communication difficult, if not even impossible, political fragmentation can have the sole certain effect of worsening the conditions in which human labour takes place and making economic progress difficult.

The grand project of the ‘United States of South America’, generously supported by Simón Bolívar, if accepted, would certainly, needless to say, have set Latin America on the path toward a glorious future. But the project displeased the landed aristocracy of Brazil, displeased the North American colonists of Virginia, and above all met with the disapproval of England, which was nevertheless a great friend of the South American insurgents. It is well known that the traditional rivalry with Spain, which had been temporarily silenced by the need to fight Napoleon, prompted England to support the revolt of the Spanish colonies. Weapons, volunteers, ships, and money, generously supplied to the insurgents, concretised British political sympathies. But it was clearly not selfless aid. British capitalism tended to favour the collapse of the Spanish empire for the same reason that drives all states to help the enemies of their imperialist rivals: the desire to create new foreign markets. Now it is clear that the unification of former Spanish America into a great confederation, as Bolívar dreamed, would have placed an obstacle in the way of British economic penetration that would not easily surmountable.

The same class interests, albeit with different objectives, drove the Creole landed aristocracy to oppose the plans for continental unity supported by Bolívar and the political forces he embodied. In the eyes of the slave owners, leaders such as Bolívar, San Martín, and Morales, who carried out their epic revolutionary exploits leading mixed armies that included, together with the Creoles, Indians and mestizos, represented a danger. Would the liberation of the slaves, the raising of the living conditions of the Indian and mestizo populations not subvert the social foundations upon which the economic regime of large landed property and plantations rested? This could not be tolerated by the landed oligarchy, which had rebelled against the Spanish colonial bureaucracy precisely because the monopoly regime and imperial taxation undermined their privileges. The slave owners had reason to fear that the political unification of the subcontinent would entail the strengthening of the democratic and interracial movement.

In this way, the slave-owning interests of Brazil's landowners and the imperialist ambitions of Great Britain coalesced against Bolívar. Not only did the ‘States of the South’ remain an unattainable dream, but even the very state formation that Bolívar had managed to cobble together split in 1821 into the three independent states of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The slave-owning landowners of Brazil set an example. Shortly thereafter, the current Central American republics (Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Nicaragua) also dissolved a state union they had formed in 1823, completing the process of dismemberment and fragmentation of the former colonial empire.

This is to say that the anti-colonial revolution in Latin America ended with the complete triumph of the landed oligarchies. But not only them. The United States initially took advantage of the dismemberment, albeit briefly, managing to gain some commercial positions in the subcontinent, but they soon had to yield the field to England. This explains how, in the second half of the last century, the management of Latin America’s economic affairs fell completely into the hands of British capitalists, closely followed by the French, Belgians, and Germans. Banks, mines, railways, telephones, power stations, coffee, cocoa, etc. were practically beyond the control of local governments.

Naturally, foreign capital investors did everything in their power to prevent any democratic reforms aimed at taking the country away from foreign industrial monopoly. For European capitalists, especially British ones, every factory that sprang up in areas under their influence meant an attack on their industrial supremacy; at best, a useless copy. Naturally, the interests of the imperialists converged with those of the landed aristocracy, who saw in the reform policies supported by democratic and radical currents a mortal danger to their privileges. Did industrialisation not mean the regression of the agrarian economy?

In this way, the landowning class, which had the Church and the army at its service, accepted that foreign imperialism, in exchange for political and military support, collected a heavy tribute, which ultimately did not affect its profits, being drawn from the sweat and blood of the working classes, oppressed by an appalling poverty that certainly is not over today.

It is understandable how the social structure of Latin America, based on the supremacy and unlimited privilege of the landed oligarchies and their political instruments, and on the absolute lack of rights for the lower classes, lasted so long. A long series of political battles, revolts, coups d’état, and often bloody civil wars could not, and did not, eradicate the hated landowning privilege, because it was supported, not only by its own forces, but also by foreign imperialist powers. Armed intervention in Latin American internal affairs was of no use to the latter, except in a few cases. It was enough to tighten the noose of economic blackmail around the necks of progressive and anti-imperialist governments that dared to question the existing order to bring about their downfall or, as was the case in most instances, to induce them to change sides.

The iron alliance between the landed aristocracy, politically represented by militarism, and foreign finance capital, with the former subject to the latter, is not unique to Latin America. The class domination of capitalism is based precisely on the identification of the interests of agrarian property and entrepreneurial capital in relation to the working classes. Naturally, the agrarian economy and the industrial economy have different rates of development, and this causes friction between landowners and industrial capitalists; but such conflicts disappear as if by magic when it comes to joining the forces of exploitation against the working classes. What has occurred in Latin America for over a century is therefore the rule, certainly not the exception, of the mechanism of capitalist exploitation. What is particular is that the fusion – above and beyond the borders and facile nationalist rhetoric of South American military regimes – of the local landowning oligarchy and foreign finance capital has kept Latin America completely outside the industrial revolution of the last century, throwing it into the condition of a financial colony of imperialism.

We will return to this topic, as well as to the social and political aspects of Latin American backwardness; for now, a few figures will suffice. Well, on the eve of the 1929 crisis, raw products accounted for at least 80%, generally more than 90%, and sometimes almost all of exports in all South American countries, while manufactured articles accounted for an almost negligible percentage in foreign sales. Even today, the value of foodstuffs and raw materials account for 90% of total exports to other parts of the world. From this emerges the purely colonial character of the Latin American economy, which, as a supplier of raw materials to foreign industries and a purchaser of industrial products, is on the same level as Africa.

For something new to mature in the Latin American social structure, there had to be at least a break in the traditional mechanism of exploitation of the subcontinent. And this happened during the Second World War. Already at the time of the First World War, the grip of the imperialist pincer had loosened somewhat, but with the sure effect of allowing the gigantic North American imperialism to wrest important financial positions from its rival capitalists in Europe. The Second World War, on the other hand, abruptly severed trade relations between Latin America and the emporiums of Western Europe. While England had to fight fiercely to save its own existence and was forced to neglect its South American financial vassals, the United States, likewise engaged in the huge conflict between the continents, could only take partial advantage of the situation. In fact, Uncle Sam’s great financial offensive took place in the post-war years and cannot be said to have ended at the present moment.

Taking advantage of the conditions of isolation caused by the war and manipulating North American capital itself, the leading forces of the anti-oligarchic coalition were laying, in some republics, the bases for national industry, especially the most important ones such as Brazil and Argentina. Thus was born the iron and steel industry, something completely new in the absolute kingdom of the haciendas and estancias. And, with the advent of large-scale industry, new political ideologies and new types of political regimes took shape, such as Peron’s ‘justicialism’, which shifted the traditional bases of the anti-oligarchic alliances. Since the end of the last century, the workers’ movement that emerged in those times had vigorously supported all the political battles of the middle classes against the landed oligarchy and the militarism that politically represented its interests. Peronism, an expression of the interests of the nascent entrepreneurial bourgeoisie, which saw itself hampered by the obtuse conservatism of the landed aristocracy, sought to win the support of the working class, and it cannot be denied that it succeeded in doing so.

Today, Latin America is in full ferment. The militarist dictatorships have collapsed everywhere except, in Paraguay and San Domingo. And this means that the centuries-old domination of the agrarian oligarchy is showing clear signs of collapse. But the turning point poses a serious danger to the workers’ movement, namely the danger of justicialism which, under the ideological cover of the struggle against the universally hated agrarian oligarchies, seeks to smuggle in interclassism, a weapon of reformist contamination of the working class.

All American Indians are most likely descended from Mongoloid populations that migrated from Siberia into Alaska around thirty thousand years ago, during the retreat of a glaciation or by exploiting a passage that no longer exists, and spread over time throughout the entire continental territory. So much so that, at the end of the 1400s, the epoch in which America returns to stable contact with Europe, three distinctions can be made:

a) Hunter-gatherer peoples. Nomads who travel across the territory hunting, or populations who periodically settle to cultivate the land (cassava and maize), then move on when the soil becomes depleted. These populations move along the Atlantic coasts of South America or across the northern prairies and are, as Engels says, in the higher stage of savagery.

‘HIGHER STAGE. Begins with the invention of the bow and arrow, whereby game became a regular source of food, and hunting a normal form of work. Bow, string, and arrow already constitute a very complex instrument, whose invention implies long, accumulated experience and sharpened intelligence, and therefore knowledge of many other inventions as well. We find, in fact, that the peoples acquainted with the bow and arrow but not yet with pottery (from which Morgan dates the transition to barbarism) are already making some beginnings towards settlement in villages and have gained some control over the production of means of subsistence; we find wooden vessels and utensils, finger-weaving (without looms) with filaments of bark; plaited baskets of bast or osier; sharpened (neolithic) stone tools. With the discovery of fire and the stone ax, dug-out canoes now become common; beams and planks arc also sometimes used for building houses. We find all these advances, for instance, among the Indians of northwest America, who are acquainted with the bow and arrow but not with pottery. The bow and arrow was for savagery what the iron sword was for barbarism and fire-arms for civilisation – the decisive weapon’ (Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State).

b) Settled tribes of farming peoples. They live mainly off the cultivation of cereals (maize, cassava, guanaco), are now settled within a territory, land ownership is collective, they are familiar with worked stone (obsidian) and pottery. They are in the lower stage of barbarism:

‘Middle Stage. Begins in the Eastern Hemisphere with domestication of animals; in the Western, with the cultivation, by means of irrigation, of plants for food, and with the use of adobe (sun-dried) bricks and stone for building. We will begin with the Western Hemisphere, as here this stage was never superseded before the European conquest. At the time when they were discovered, the Indians at the lower stage of barbarism (comprising all the tribes living east of the Mississippi) were already practicing some horticulture of maize, and possibly also of gourds, melons, and other garden plants, from which they obtained a very considerable part of their food. They lived in wooden houses in villages protected by palisades’.

c) Developed political organisations in Central America. The most important are undoubtedly the population concentrations in the three great domains of the Aztecs, the Maya, and the Incas. Despite their differences, they share a number of characteristics:

These three Central American populations, albeit in different forms, cultivated the land in common. Despite having a long independent development from the rest of humanity, they tend to retrace the necessary evolution of the human species. In this we see reconfirmed the materialist interpretation of history given by Marxism. We know well that the period of common ownership of land is a very long phase, which the entire human race must go through:

‘A ridiculous presumption has latterly got abroad that common property in its primitive form is specifically a Slavonian, or even exclusively Russian form. It is the primitive form that we can prove to have existed amongst Romans, Teutons, and Celts, and even to this day we find numerous examples, ruins though they be, in India. A more exhaustive study of Asiatic, and especially of Indian forms of common property, would show how from the different forms of primitive common property, different forms of its dissolution have been developed. Thus, for instance, the various original types of Roman and Teutonic private property are deducible from different forms of Indian common property’ (Marx, ‘Critique of Political Economy’, in ‘India, China, Russia’).

In Mexico, this form of common land ownership is called calpulli. This is a grouping of families organised into villages that refer to a single chief or a series of chiefs, who establish the periodic distribution of land among the individual families. The chiefs have the right to use personal services and the products of the land as compensation for their work in administering the social life of the Commune. The calpulli is therefore nothing other than a gens, or a confederation of gens, or a tribe.

In Peru, however, given the different environmental conditions, the gentile federation, known as ayllu, tends to collectively own not only the land but also a whole range of productive activities: grazing and potato cultivation in the highlands, maize cultivation on the hillsides and cotton in the plains, fishing on the coasts. All these complex activities are managed in common by a single consanguineous group, a gens or a lineage; while the villages and towns are formed on the territory in much the same way as those formed in the Middle Ages by the Germans, who organised themselves into marches or confederations of villages. Part of the land, pastures, and harvest belongs to the Inca. The chiefs of the ayllu establish the periodic distributions of land among the individual families.

‘In India, the household community with common cultivation of the land is already mentioned by Nearchus in the time of Alexander the Great, and it still exists today in the same region, in the Punjab and the whole of northwest India. Kovalevsky was himself able to prove its existence in the Caucasus. In Algeria it survives among the Kabyles. It is supposed to have occurred even in America, and the calpullis which Zurita describes in old Mexico have been identified with it; on the other hand, Cunow has proved fairly clearly that in Peru at the time of the conquest there was a form of constitution based on marks (called, curiously enough, marca), with periodical allotment of arable land and consequently with individual tillage’ (The Origin...).

Such a formal system of tribute labour allows the colonisation of uncultivated areas in the Andes through the displacement of entire groups of families, or accelerates the social division of labour by transforming peasants into artisans working for the Inca, who monopolise the cultivation of valuable products such as coca. Finally, for the construction of social works (roads, temples, public buildings, irrigation works), there is the myta, or periodic, gratuitous, and temporary labour service; in particular, the myta is used to exploit mineral resources. Among the Inca, the already centralised political organisation has great importance as a factor in productive development. Just as in Imperial China, where the state regulated the flow of water by controlling rice cultivation, in the Andes the land is cultivated in terraces, so that every reclamation and cultivation work presupposes a central plan and the collaboration of a large part of the population.

‘[Men] relate naïvely to [the land] as the property of the community, of the community producing and reproducing itself in living labour. Each individual conducts himself only as a link, as a member of this community as proprietor or possessor. The real appropriation through the labour process happens under these presuppositions, which are not themselves the product of labour, but appear as its natural or divine presuppositions. This form, with the same land-relation as its foundation, can realise itself in very different ways. E.g. it is not in the least a contradiction to it that, as in most of the Asiatic land-forms, the comprehensive unity standing above all these little communities appears as the higher proprietor or as the sole proprietor; the real communities hence only as hereditary possessors. Because the unity is the real proprietor and the real presupposition of communal property, it follows that this unity can appear as a particular entity above the many real particular communities, where the individual is then in fact propertyless, or, property – i.e. the relation of the individual to the natural conditions of labour and of reproduction as belonging to him, as the objective, nature-given inorganic body of his subjectivity – appears mediated for him through a cession by the total unity – a unity realised in the form of the despot, the father of the many communities – to the individual, through the mediation of the particular commune. The surplus product – which is, incidentally, determined by law in consequence of the real appropriation through labour – thereby automatically belongs to this highest unity. Amidst oriental despotism and the propertylessness which seems legally to exist there, this clan or communal property exists in fact as the foundation, created mostly by a combination of manufactures and agriculture within the small commune, which thus becomes altogether self-sustaining, and contains all the conditions of reproduction and surplus production within itself. A part of their surplus labour belongs to the higher community, which exists ultimately as a person, and this surplus labour takes the form of tribute etc., as well as of common labour for the exaltation of the unity, partly of the real despot, partly of the imagined clan-being, the god. Now, in so far as it actually realises itself in labour, this kind of communal property can appear either in the form where the little communes vegetate independently alongside one another, and where, inside them, the individual with his family work independently on the lot assigned to them (a certain amount of labour for the communal reserves, insurance so to speak, and to meet the expenses of the community as such, i.e. for war, religion etc.; this is the first occurrence of the lordly dominium in the most original sense, e.g. in the Slavonic communes, in the Rumanian etc. Therein lies the transition to villeinage [Frondienst] etc.); or the unity may extend to the communality of labour itself, which may be a formal system, as in Mexico, Peru especially, among the early Celts, a few clans of India. The communality can, further, appear within the clan system more in a situation where the unity is represented in a chief of the clan-family, or as the relation of the patriarchs among one another. Depending on that, a more despotic or a more democratic form of this community system. The communal conditions of real appropriation through labour, aqueducts, very important among the Asiatic peoples; means of communication etc. then appear as the work of the higher unity – of the despotic regime hovering over the little communes. Cities proper here form alongside these villages only at exceptionally good points for external trade; or where the head of the state and his satraps exchange their revenue (surplus product) for labour, spend it as labour-fund’ (Marx, Grundrisse, IV).

Essentially, the class division of these large barbaric societies is similar. At the top is what historiography usually refers to as the ‘emperor’, but who would be better called a military chief:

‘The leader of the army (basileus). Marx makes the following comment: European scholars, born lackeys most of them, make the basileus into a monarch in the modern sense. Morgan, the Yankee republican, protests. Very ironically, but truly, he says of the oily-tongued Gladstone and his Juventus Mundi: “Mr. Gladstone, who presents to his readers the Grecian chiefs of the heroic age as kings and princes, with the superadded qualities of gentlemen, is forced to admit that ‘on the whole we seem to have the custom or law of primogeniture sufficiently, but not oversharply defined’” (...)

‘In addition to his military functions, the basileus also held those of priest and judge, the latter not clearly defined, the former exercised in his capacity as supreme representative of the tribe or confederacy of tribes. There is never any mention of civil administrative powers; he seems, however, to be a member of the council ex officio. It is therefore quite correct etymologically to translate basileus as Koening, since Koening (kuning) is derived from kuni, kunne, and means head of a gens. But the old Greek basileus does not correspond in any way to the present meaning of the word “king” (...) Like the Greek basileus, so also the Aztec military chief has been made out to be a modern prince. The reports of the Spaniards, which were at first misinterpretations and exaggerations, and later actual lies, were submitted for the first time to historical criticism by Morgan. He proves that the Mexicans were at the middle stage of barbarism, though more advanced than the New Mexican Pueblo Indians, and that their constitution, so far as it can be recognised in the distorted reports, corresponded to this stage: a confederacy of three tribes, which had subjugated a number of other tribes and exacted tribute from them, and which was governed by a federal council and a federal military leader, out of whom the Spaniards made an “emperor”’ (Origin...).

Then there is the class of nobles (or warriors) and the class of priests, generally belonging to the lineage of the ‘emperor’; the village chiefs, i.e. the chiefs of the tribes subject to the ‘emperor’; the peasants who collectively cultivate the land; a class of slaves is also forming, that is, of those born into slavery or captured in war; and there is a class of artisans, both free and enslaved, who serve the nobility. There are also merchants, to be understood more as a class of barterers, as they must keep the various parts of the empire connected through the exchange of simple goods; since in this mode of production commodities are not produced but consumable goods, production is not for the market, but, as we have seen, an insignificant surplus is transformed into commodity:

‘The aim of this work is not the creation of value (...) rather, its aim is sustenance of the individual proprietor and of his family, as well as of the total community’ (Marx, Grundrisse).

Money is known, but it does not have the importance it has in those economic systems where production is for the market; therefore, it exists but has not yet subjugated society.

‘It cannot, indeed, be denied that pre-capitalist societies disclose other modes of distribution, but the latter are interpreted as undeveloped, unperfected and disguised, not reduced to their purest expression and their highest form and differently shaded modes of the natural distribution relations. The only correct aspect of this conception is: Assuming some form of social production to exist (e.g., primitive Indian communities, or the more ingeniously developed communism of the Peruvians), a distinction can always be made between that portion of labour whose product is directly consumed individually by the producers and their families and – aside from the part which is productively consumed – that portion of labour which is invariably surplus-labour, whose product serves constantly to satisfy the general social needs no matter how this surplus-product may be divided, and no matter who may function as representative of these social needs’. (Marx, Capital, Volume III).

These are therefore immense societies that have not yet emerged from extremely advanced forms of gentile organisation. In them, the characteristics of the State, embryonically already present, tend to subjugate society and dissolve the gens, but for this to happen, epochs of social conflict between classes are necessary, which demonstrate the need for an organism that appears to be above the classes themselves, the State, which we know to be a tool of the ruling class. But Marxism does not deny that it presents itself as a form dictated by precise social needs, and that only over time does such a form pass into class oppression.

‘As men originally made their exit from the animal world – in the narrower sense of the term – so they made their entry into history: still half animal, brutal, still helpless in face of the forces of nature, still ignorant of their own strength; and consequently as poor as the animals and hardly more productive than they. There prevailed a certain equality in the conditions of existence, and for the heads of families also a kind of equality of social position – at least an absence of social classes – which continued among the primitive agricultural communities of the civilised peoples of a later period. In each such community there were from the beginning certain common interests the safeguarding of which had to be handed over to individuals, true, under the control of the community as a whole: adjudication of disputes; repression of abuse of authority by individuals; control of water supplies, especially in hot countries; and finally when conditions were still absolutely primitive, religious functions. Such offices are found in aboriginal communities of every period – in the oldest German marks and even today in India. They are naturally endowed with a certain measure of authority and are the beginnings of State power.

‘The productive forces gradually increase; the increasing density of the population creates at one point common interests, at another conflicting interests, between the separate communities, whose grouping into larger units brings about in turn a new division of labour, the setting up of organs to safeguard common interests and combat conflicting interests. These organs which, if only because they represent the common interests of the whole group, hold a special position in relation to each individual community – in certain circumstances even one of opposition – soon make themselves still more independent, partly through heredity of functions, which comes about almost as a matter of course in a world where everything occurs spontaneously, and partly because they become increasingly indispensable owing to the growing number of conflicts with other groups. It is not necessary for us to examine here how this independence of social functions in relation to society increased with time until it developed into domination over society; how he who was originally the servant, where conditions were favourable, changed gradually into the lord; how this lord, depending on the conditions, emerged as an Oriental despot or satrap, the dynast of a Greek tribe, chieftain of a Celtic clan, and so on; to what extent he subsequently had recourse to force in the course of this transformation; and how finally the individual rulers united into a ruling class. Here we are only concerned with establishing the fact that the exercise of a social function was everywhere the basis of political supremacy; and further that political supremacy has existed for any length of time only when it discharged its social function’ (Engels, Anti-Dühring).

In conclusion, although its forms of property and social evolution are known to Marxism and mirror those already experienced by the rest of humanity, the American continent, shortly before coming into contact with Europe, gives the impression of being a planet unto itself; which has embarked on an autonomous technical and social development. In fact, these are forms of society that the rest of humanity has already surpassed for millennia. Do not be misled by the extreme complexity of these pre-Columbian ‘empires’, their high degree of civilisation, and the fact that they can organise millions of people (between 30 to 80 million according to some studies). These were extremely fragile and backward modes of production with respect to the nascent European mercantilism, in which the now established civilised age even heralds the advent of capitalism.

At the end of the fifteenth century, Spain has just been reunified with the marriage of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, the Arabs having been definitively expelled from Granada. Now the Strait of Gibraltar is controlled by Christians: Spain to the south and Portugal to the north, after the capture of Ceuta and Tangier. The Iberian economic and social structure is backward compared to the rest of Europe. The crowns, especially the Castilian one, base their power on a class of nobles from the highlands, who live off taxes, the Mesta, derived from transhumance grazing: a very profitable activity since there was great demand for wool in Flanders and Italy.

The reconquest of the three major Iberian kingdoms (Castile, Aragon, and Portugal) took place with the granting of the territories seized from the Moors to the warrior nobility and with the expansion and consolidation of the Mesta in the new regions; this led to the outright dispossession of the lands of the small Arab peasants, who were technically among the most advanced in Europe. This is the only explanation for why the reconquest led to an entire era of peasant revolts and rebellions by artisans against the nobility.

With reunification begins that process which will therefore lead to the expulsion of the Moriscos and Jews, who represented the most advanced part of the country, those artisans and small farmers who, in the rest of Europe, will give rise to the bourgeoisie.

During this same period, manufacturing is developing in Italy, Flanders, the Netherlands, France, and England, but it is still an activity subordinated to the great merchant families. The two major Italian maritime republics, Genoa and Venice, have control over the western and eastern zones of the Mediterranean respectively. Genoa controls the gold route, linking the coast of North Africa, Ceuta, and Tunis, where caravans arrive after crossing the desert to connect the Central African empires to the Mediterranean, with Central Europe. Venice controls the spice route, which starts from the Indies and is managed by the Chinese as far as Calcutta, then by the Arabs as far as the Red Sea, and finally by the Venetians, who buy the spices on the Egyptian and Syrian markets to distribute them throughout the European continent. The importance of gold is due to the emerging need for merchants to have a general equivalent valid for all international trade, while the importance of spices is due to the need to preserve meat, through their bactericidal power.

The world, therefore, is an ensemble of closed areas, but at the same time not entirely isolated from one another; they remain in equilibrium because none are able to gain the upper hand over the others, a task that will be carried out in the following centuries by the European bourgeoisie. For its part, America has an independent development, naturally outside these exchanges between continents, which have been painstakingly created in the rest of the world.

Europe is in the phase of formal subsumption of labour to capital. Bankers, usurers, by indebting and ruining large landowners and small producers, appropriate the land and conditions of labour of small artisans and of the peasants themselves. For these reasons, the crowns are forced to take upon themselves the burden of the commercial wars in order to cope with their progressive indebtedness. Ultimately, this is the main cause of the great discoveries of the 15th century. The very Atlantic propensity of Portugal and Spain is, initially, only a sign of weakness: unable to undermine the hegemony of the major Italian maritime republics, an alternative route was sought to reach the markets of the Indies, the fulcrum around which all maritime trade revolved. Even when Asia could be reached by circumnavigating Africa, Venice remained, up until the end of the 17th century, the main supplier of spices to Europe.

Portugal is a typical example of the subordination of the State to usurious and mercantile capital: it has a port on the Atlantic, Lisbon, which allows it to manage the connections between Northern Europe, the crucial market of Amsterdam, and Africa; it controls part of the Strait of Gibraltar; it has a nobility indebted to the great European bankers. This is why, at the beginning of the 1400s, Portuguese merchants customarily attended the annual fairs held by African traders, searching especially for gold to mint coins. In doing so, the Portuguese gradually explored the West African coast, increasingly coming into contact with black peoples.

But the best business came from the discovery of African pepper and malagueta, both cheap spices. Later, armed and fortified strongholds began to be built along the African coast (Cantor, Sao George de Mina) with the aim of defending the emporiums that merchants gradually established under the protection of the army. By the end of the century, the Portuguese had already rounded the Cape of Good Hope, realising that they had entered the Indian Ocean controlled by the Arabs. Portuguese merchants traded manufactures, bought cheaply in Flanders, London, and Lyon, mainly for gold, slaves, and spices. It is clear how in this process capitalist manufacturing consolidates itself: gold passed through Lisbon to end up in the coffers of German bankers, who had advanced capital for the great explorations, or it was used to purchase cloth, canvas, silk, and weapons produced abroad. The crown’s army guaranteed the monopoly of African trade through the Casa de Guinea; then, after 1500, it would attempt to guarantee the monopoly of trade with the East Indies through the Casa de India.

When historical necessities are pregnant with great undertakings, the man of genius emerges. Such is the case with Columbus, who represents the experience of Genoese navigators and the scientific consciousness of his time: that the Earth was spherical was already known to all serious scientists.

To attempt the enterprise, Columbus first turns to Portugal. The refusal he receives was mainly due to the lack of interest the Portuguese have in a western route to the Indies, since the possibility of the eastern route is by now more than evident. Portuguese ships, in fact, regularly connect with the Indian Ocean, using the trade winds and counter-trade winds according to the latitude. Thus, after initial approaches, a commercial war is successfully waged to establish a trading post in Calcutta. The venture was such that Vasco da Gama, commander of this expedition, would return home with a cargo of Indian pepper worth 15 times the costs incurred of equipping the fleet of 20 ships that had set out on the enterprise (1459).

Columbus must therefore turn to another Atlantic power; the political circumstances of the time meant that it was Spain, strengthened by its recent victory over the Arabs, that would provide him with the port, the ships, and the men. Moreover, until shortly before his departure, Columbus also had contacts with England.

From the very first crossing, the correct route is taken, the direct one, which will remain the same for the entire duration of the voyage. This indicates that no random route is being sought, as the technical knowledge required for the discovery of America is now well established. English sailors had been venturing out into the open sea from Bristol for some time already, while nautical charts indicate islands scattered across the Atlantic with names that would become significant, Antilles, Brazil: it cannot be ruled out that some ship reached the American coast before 1492. Moreover, in 1500, Cabral would happen to discover Brazil by chance, having exploited the south-east trade wind too much while bringing reinforcements to Vasco da Gama’s expedition.

It would take about twenty years to understand the real significance of the discovery of the West Indies. During this period, a series of events took place that would have a considerable impact on subsequent historical development. In 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas is signed, by which Spain and Portugal divide the colonies along a meridian line. In 1503, the Casa de Contratación is founded in Spain, which, following the Portuguese model, is responsible for managing the monopoly of trade with the Indies: the king reserves the ownership of one fifth of what his subjects will be able to obtain from the exploitation of the colonies. By the early 1500s, it is already clear that it is another continent; all the Atlantic coast of America is explored by Vespucci in search of a passage to the East Indies, which would be found in 1519 by Magellan. During this period, the first Spanish settlements have been formed in the Antilles, first in Puerto Rico, then in Haiti and Cuba; the Portuguese have also settled in Brazil; by now there are direct or indirect contacts with the Central American indigenous populations in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Spaniards arrived in America with the intention of appropriating the treasures of the cities and replacing the rule of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca chiefs; in doing so, they reproduce the same relations of production that they had established during the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula: territories are granted to the faithful servants of the crown.

This was therefore not the same method that would later be used by the English, Dutch, and French; the problem for the Spanish is not to expel surplus populations that have formed as a result of the implantation of the capitalist mode of production, but to exploit the American treasures as much as possible to pay off the growing indebtedness of the aristocracy to the German and Dutch usurer bankers. It was not, therefore, the particular greed of the Spaniards but the particular economic relations of Europe that imposed medieval-style personal servitude upon the Indians, even worse than what they were used to.

How was it possible that expeditions of ‘adventurers’, even if well armed, could have shattered social organisations of millions of people? That this could not fail to happen can be explained by the backwardness of the economic structure of the pre-Columbian ‘empires’ compared to the incipient European capitalism represented by the Spanish. On the other hand, the fact that the conquest took place in just a few years, something that in any case is only partially true, can be explained by the overlapping of causes of a structural order with those of a contingent political order: the internal struggles that, at the beginning of the 1500s, were troubling these Central American populations were opportunistically exploited by the conquistadors.

Cortés conquered Mexico in early 1519. To do so, he took advantage of the rebellion of some populations in the province of Texala against Montezuma II; by virtue of these alliances, Cortés managed to avoid an ambush set up by the Aztec army and counterattacked to destroy the indigenous militias using his cannons; by the time he entered the Mexican capital, Tenochtitlan, he had all the rebellious populations behind him and was able to take the ‘emperor’ prisoner. The Spanish then proceeded to sack the capital, provoking the rebellion among the indigenous populations that had supported them until then; the conquistadors were thus driven out by a revolt, making a second expedition necessary, in which Tenochtitlan was once again besieged, bombarded, and finally taken and sacked.

More difficult was the conquest of Yucatan, where the rule of the Maya was consolidated and it was not possible to turn the indigenous populations against their chiefs. Instead, the opposite happened: the populations rebelled against the Spanish advance. It took a quarter of a century to subdue the Maya in a veritable bloodbath.

The Inca ‘empire’ at the time of the Spaniards’ arrival was in the throes of a serious dynastic crisis: two claimants were vying for the throne. In 1531, Pizarro, after two failed attempts, reached Peru only on the third. He allied himself with the ‘illegitimate’ pretender, having the brother, the legitimate heir, assassinated; then, after appropriating the imperial treasure, he decided it best to eliminate the other one as well. Thus Pizarro had the fratricidal Atahualpa tried as a usurper, idolater, and polygamist and had him executed. The following period was marked by a whole series of rebellions, both among the rabble that had followed Pizarro and among a section of the Indians themselves. The latter would form an Inca community in the Sierra, which would be able to remain isolated from the Spanish until 1572.

In 1535, the conquest of Chile begins, but the Spanish, after their initial successes, suffer a series of defeats at the hands of the Araucanian peoples and are forced to sign a peace treaty, which will be respected for 200 years.

The Spanish voraciously set about plundering the treasures of the Indians; but the spoils of war, however vast, are only one aspect of the conquest, the other is the subjugation of the populations. Thus is born the encomienda, that is, the concession granted by the king to the conquistadors of the right to exploit the lands and the natives residing on them. The land and the natives are placed in the custody of the encomendero, who could dispose of them as he pleased, collecting taxes or imposing personal servitude.

This form of ownership can be traced back to Asiatic or feudal models and presupposes the reversibility of the concession. Ultimately, it is the sovereign who is the owner of the colonies, which are given in trust; the trustee (or encomendero) can exploit them by paying a fifth of the profits to the Spanish State. Initially, the encomienda is used as a reward for the military services of the conquerors and is normally granted for three generations; this is not new, as the same method had been used during the expulsion of the Moors. Cortés, for example, grants some territories in encomienda to his own soldiers and is himself the largest encomendero in Mexico. However, subsequent generations, even though they would inherit immense territories from the conquistadors, will have to increasingly submit to the authority of the colonial bureaucracy, directly appointed by Spain.

At first, the Spanish simply intended to superimpose themselves over the rule of the indigenous chiefs, but soon the demands of the European market dictated their own terms to the colonies.

New techniques unknown to the Indians are introduced, such as the plough, the wheel, and new species of animals such as the horse, the sheep, the ox, and the pig, as well as new crops such as wheat. Soon, typical Indian crops (corn, potatoes) proved to be of little importance to the Spanish, who therefore began to plant more profitable crops, such as sugar cane and tobacco, in high demand in Europe. Mining, especially of silver and mercury, is also intensified. This new production system is implemented at the expense of the Indians, forced into hard shifts of unpaid or semi-unpaid labour.

Historians love to discuss the inhumane and coercive nature of the encomienda and are always embarrassed by the right that the Pope and Catholic kings arrogated to themselves in entrusting the Indians to the barbarous conquistadors; Marxism is certainly not afraid of personal servitude, nor does it consider its transformation into a tax in kind or in money to be less exploitative, if anything, it considers these changes to be signs of an occurred change in the economic structure.

The encomienda immediately posed the question of its heredity, which over time would increasingly mean the possibility of selling the land. It is clear that the encomendero, not being the owner of the land, could not sell it. For its part, royal legislation tended to apply the rule of two or three generations, which meant that long inheritance disputes dragged on between the heirs and the Spanish crown. Legal representatives carefully studied the cases family by family in order to establish for how many generations one had been in possession of the encomienda, because the royal concession varied from case to case without a precise rule. There were even those who were entitled to four generations for special merits or who obtained ownership. However, towards the end of the 1600s, all the large encomiendas had returned into the possession of the crown, which once again gave them in concession for a short time; sometimes, the encomendero was given only the income from an encomienda, without ever taking possession of it, while State officials were responsible for running the enterprise and collecting taxes. Ultimately, until the end of the 18th century, it is the crown that manages the colonial income and establishes the concession rights.

As good thieves, the Spanish did not have much regard for the forms of exploitation of the Indians. Everything was lawful: from domestic service to extortion of corvée, forced labour in artisanal workshops, to servile labour in the mines. For example, in Guatemala, repartimientos were used, whereby village chiefs (the caciques) had to provide the Spanish with a certain number of Indians according to the colonists’ requests. The Indians had to present themselves with their work tools and enough food for a week, which was the time they had to work, the reward was little more than symbolic. It was a kind of corvée already in use under the Maya, in this case the Spanish did nothing other than replace the old masters.

But this enslavement took on aspects much more brutal in the case of labour in the mines of Potosí, in Peru. Here, forced labour was still called myta, as in the time of the Incas, only that now it meant working for 40 days in the mercury mines and 4 months in the silver mines.

During this period, the large latifundium began to form through the establishment of sheep and cattle breeding, and if they had been able to, the Spanish would have reintroduced also the Mesta, but instead had to limit themselves to depopulating the lands of the indigenous people, as they had done in the past with those of the Arabs. Thus is formed a class of impoverished peasants, the peons, forced to live on the latifundium as serfs by birth or by debt.

Since there are no spices in the American colonies, the Europeans’ interest turns to precious metals and crops such as sugar and tobacco, which were in high demand in the Old World. Large silver deposits are discovered immediately, especially in Peru, near the ancient capital Cuzco. In Huancavelica, on the other hand, there is mercury, which in turn serves in the silver extraction process.

Very important are the repercussions of colonial activity in Europe. This gave rise to the Spanish carrera, the trade link between the mother country and the West Indies, through the Casa de Contratación, which was supposed to ‘secure the gold, silver, jewels, and other things coming from the Indies’, the monopoly on American trade was exercised, which departed from Seville and Cadiz and arrived at only three American ports: Veracruz, Cartagena, and Portobelo. Immense fortunes in silver flowed into Spain, but they served to pay the interests to German bankers, the Fuggers, or to purchase commodities to be taken to America from the nascent manufacturers of Flanders, Holland, and England. The Casa de Contratación itself, like its Portuguese counterpart, was increasingly dominated by Dutch, Flemish, French, and Venetian merchants.

Industrial capital is the real winner of the commercial wars of the late Middle Ages. The mercantilist delusion that wealth consists in the simple accumulation of precious metals is cruelly disproved as gold and silver lose in value due to their excessive quantity. An inflationary period begins in Europe, centred in the Iberian countries, to the extent that Spain, which in the meantime has absorbed Portugal, is forced to declare ‘bankruptcy’ in 1577.

At the same time, new crops imported from America allow for an increase in the yield of lands until then not very fertile because it is unsuitable for growing cereals: the classic example is the introduction of the potato in Germany.

And yet we are in the phase of maximum Spanish power in the world, which dialectically prepares the rise of the bourgeois nations, for whom the exploitation of colonies will be of fundamental importance.

The consequences of the arrival of the Spanish on the indigenous populations are truly catastrophic. The inability of the peasants of the pre-Columbian communes to adapt to work in the mines or on tropical plantations, the new dietary habits imposed on the mytayos, based on spiced pork, at a time when the collapse of the old production system causes agricultural production to plummet and, above all, the intensification of exploitation at all levels, are the factors that lead to the spreading of a whole range of infectious diseases, already known in Europe, but which the Indians were unprepared to confront.

The worsening living conditions weakens the indigenous people’s immune systems, so that in less than a century more than half of the Central American population dies of typhus, smallpox, or measles. This is the cause of the beginning of the importation of black people, better suited to surviving the diseases, the privations, and the slavery. Thus, sugar production in the Antilles intensifies through the slave labour of Negroes. The slave trade begins, which will last until the end of the eighteenth century, tearing from Africa some 50 million people.

If, as is true, the history of the Americas from the first moment was directly linked to the development of European capitalism, then we can only explain the development of colonialism in a global sense. It is therefore necessary to recall some historical concepts in order to better organise the analysis of the economic and social structure of Latin America at the end of the eighteenth century.

The emerging nations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe are Great Britain and France. The former has already undergone its bourgeois revolution (Cromwell), subjugated the nascent commercial power of Holland, and then began to dismantle the great Spanish power, which, throughout the seventeenth century, remains the world hegemon. It is with the destruction of the Invincible Armada (1588) that the beginning of the Atlantic inclination of Great Britain and the decline of Spain is dated.

France, for its part, through the policies of Louis XIV and Louis XV, of support to the great financial and mercantile bourgeoisie, increasingly replaces Spain in the predominance of Central and Mediterranean Europe. In fact, trade between Spain and America is in the hands of merchants of Lyon and Bordeaux.

As we saw, Spain’s takeover of the American colonies does not mark the beginning of a bourgeois development of its economy; but, although, throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Spain is the most important power on the globe, its strength is purely military and is based on debt to the great European bankers. Spain takes possession of the colonies in the name of the nascent European bourgeoisie, this process subsequently does not stop and comes to an end with the total downsizing of Spain in the nineteenth century.

This state of affairs is also reflected in the method of exploitation that Spain adopts in its territories beyond the Atlantic. The warrior caste, which intends to dominate Europe, only needs money to finance its armies. Gold and silver are in Latin America; therefore, for two hundred years, the colony will be organised solely for the purpose of mining. Once a year, a convoy of ships departs for the Americas from Seville, then from Cadiz. A fleet loaded with manufactures, mostly from France, and with foodstuffs, requested by the Spaniards in the colonies. After calling at the three American ports authorised for trade (Cartagena, Veracruz, and Portobelo), where the metals extracted from the mines are collected, the ships return to the homeland laden with coins of silver and gold. The king has the right, as tax, to one fifth of the value of the commodities transported and one fifth of the value of the amount of silver extracted in the Americas.

Within these rigid canons of economic exploitation, Latin America could only develop the mining sector. In particular, the nerve centres of the empire are Peru and Mexico, where huge silver deposits are discovered. The mines are exploited through forms of personal servitude such as repartimiento and encomienda, whereby the Indians provide forced labour to the white rulers.

Smuggling, especially by the English, Dutch, and French, develops on the borders of the pachydermic empire. Piracy – so dear to early twentieth century novelists – is merely the first attempt by the young Atlantic commercial powers to undermine Spanish monopoly in Latin America. Piracy aims to achieve two objectives. The first is to get their hands on the enormous loads of silver which come back from the colonies every year (we are in the era where the bourgeoisie uses precious metals as an international general equivalent). The second is to connect directly to new markets, without the intermediation of the Spanish royal bureaucracy.

For these reasons, pirate and buccaneer bases in the Antilles are often commercial centres. Merchant-smugglers stop outside territorial waters to trade with ships coming from the continent. All this is possible because Spain is, in terms of production, backward compared to the two leading European states on the Atlantic. The episodes of this advance in the seventeenth century seem insignificant compared to the Spanish mastodon, but in the eighteenth century they would prove to be fundamental.

Already towards the middle of the 16th century, French pirates arrive to conquer Cuba and demand from it a ransom; in the same period, Francis Drake is commissioned by the English crown to organise piracy in the Antilles: his capture of the Spanish convoy from the mines of Peru during the attack on Panama in 1573 remains famous. In 1604, the French settle in Guyana. In 1620, the English settle in Barbados; in the same period, the French conquer Martinique and Guadeloupe. By 1625, the French and the English have now occupied the Lesser Antilles. In 1628, it is the Dutch who capture the annual convoy of Mexican silver, coming from Veracruz. In 1630, the buccaneers establish their base on the island of Tortuga. In 1634, the Dutch take possession of Curacao. Great Britain conquers Jamaica and makes from it the centre of piracy. Morgan was the governor of Jamaica, but the anti-Spanish European nations were all implicated in his ‘illegal’ trades and profited from them. In 1697, France and Great Britain agree to divide Santo Domingo.

Throughout the seventeenth century, however, these advances fail to substantially undermine the power of Spain in Latin America. The system, organised by the conquistadors upon their arrival, remains fundamentally intact until the 18th century. Encomienda and repartimiento are the bases of the exploitation of the indigenous population’s labour: repartimiento imposes the exploitation of the mines, while encomienda organises livestock farming and agriculture to support the same mines.

Even in the relatively slow development of agricultural production, one observes the concentration of land in the hands of a few families of landowners, while it is always the crown to guarantee the property, understood as a personal concession. The large hacienda is formed, a phenomenon that initially originated in Mexico but tends to spread to the rest of the West Indies. The haciendas presuppose the expropriation of village community lands, actual confiscations carried out in the name of the crown under the most varied pretexts: for example, villages that cannot prove a right of ownership of the land are expropriated.

Beyond the brutality and inherent contents of backwardness of the methods used by Spanish landowners, we see in these processes of land concentration not a return to the Middle Ages, but a gradual takeover of the colony by the world market. The overcoming of the village commune – given the capitalist relations that already existed in the seventeenth century – was posed either in the sense of its transformation into large-scale personal servitude or the outright decimation of the Indians. Latin America could only retrace the necessary path of the brutal history of humanity.

The Spanish introduced the encomienda and repartimiento, progressive forms with respect to pre-Columbian communitarianism. With the development of the productive forces, the encomienda turned into peonage, an already bourgeois form of land exploitation. Peonage would form that mass of propertyless slaves who are the basis for the introduction of capitalism under every sky. The Yankees of North America instead – once the dispute with the Southern States was resolved – chose the more radical path of the annihilation of the indigenous communities: they wiped the Red Indians off the prairies in order to organise the capitalist mode of production.

The 18th century is the century that anticipates the definitive affirmation of the bourgeoisie on a European and global scale. In Latin America, it is the century that paves the way for the definitive destruction of the Spanish colonial system, which will have its end in 1825 with the wars of national liberation. The superiority of the colonial development model of the Anglo-French bourgeoisie over the Spanish landowners is now evident. The Antilles are the centre of this confrontation: from a hub for smuggling and piracy, they are transformed into lands producing precious raw materials. Sugar, cocoa, coffee, and indigo are produced in the Caribbean regions for consumption in Europe. Plantations are, therefore, introduced to meet the demands of the European market with European capital; trade is managed by the Europeans; black labour power is supplied by the Europeans; the commodities exchanged for raw materials are supplied by the Europeans. It is a huge business in which the wealth accumulated in capital is always controlled by the bourgeois metropolises. The entire economy of the Antilles is organised around sugar production.

The famous triangular trade is organised. Slave ships set sail from Bristol, Liverpool, or Bordeaux loaded with manufactures, especially cloth and weapons, which were in high demand in Africa; according to their needs or the political favours they enjoy, they go to the African coast of the Atlantic, where the first deal is made with indigenous merchants, controlled by some recognised local authority. The stowage of the black people could take up to four months. Then they set sail for the Antilles, where the sugar cane plantations require a continual replenishment of slave labour: on average, a slave does not live in captivity for more than ten years, so every year the owners must write off a tenth of their human capital, every ten years the black population is completely replaced by other slaves. This gives an indication of the dramatic nature of the phenomenon.

Slave Trade and Commerce in the Antilles in the 18th Century

(R.Anstey, The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1810, London 1975)

Although no more than 10 or 15 million Negroes arrive at the ports of the Americas, the devastation of the trade in Africa causes the loss of 40-50 million lives. Many Negroes die from illness or suicide on the ships, but, above all, it is the African internal wars, to procure slaves for the slave traders, that cause the decimation of entire populations. Once they set sail for the Antilles, the slaves are sold and sugar, which is in great demand in Europe, where the possibility of extracting it from beetroot has not yet been discovered, is loaded onto the ships.

In the eighteenth century, the European market for sugar and other colonial products is tacitly divided between England and France. The former, in addition to being a major consumer, manages the northern market, with the Netherlands, Denmark, and the Scandinavian countries, as far as the cold lands of the tsars, while the latter, the central European market through Bordeaux and the Mediterranean market through Marseille. If everything appears to be done in the interests of the commercial bourgeoisie, which dominates the alliance with the industrial bourgeoisie, it was ultimately the latter that sees in the strengthening of trade with Africa and with consolidated America its manufacturing framework. The commercial companies directly manage the economic organisation of the plantations by advancing capital to the planters – chronically indebted to Europe and constantly seeking letters of credit, cashable on the London Stock Exchange. Nevertheless, it is the factories of London and Liverpool that are preparing the great leap of the industrial revolution.

The Caribbean sugar business caught the Spanish economy unprepared. Cuba, for example, is a supplier of meat to the rest of the Antilles islands up until the first half of the eighteenth century. However, although less dynamic compared to the rest of America, the Spanish colonial economic structure is also evolving towards capitalism.

In Peru, the silver mines once used by the Incas are running out, but at the same time, livestock breeding is developing in the Argentine Plata, originally established to supply meat to Peruvian miners, then organised to meet the demand for leather in Europe. It seems that in the eighteenth century, the value of an ox’s hide in Buenos Aires was equal to that of its meat. In the Orinoco area, around the cocoa plantations – which do not allow for the same business opportunities as sugar plantations – extensive livestock breeding is also organised. In Mexico, on the other hand, mining is much more profitable, especially in Potosí, and it is around it that subsistence farming and livestock breeding are organised. Trade is managed through the Spanish monopoly, with the leather, cocoa, and silver merchant guilds enriching themselves and maintaining the imperial administrative structure and the crown itself.

A Creole ruling class is forming, made up of Spaniards now settling in America and who do not always share the same interests as the imperial administration. The age of piracy is now over, England has imposed the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) on Spain, obtaining a monopoly on the slave trade with the Spanish colonies, the Asiento, and the possibility of adding its own convoy of merchant ships to the Spanish fleet. The annual fairs of the three ports of Central America and Buenos Aires are thus legally opened to European trade. On the other hand, smuggling is effectively institutionalised in some Spanish viceroyalties. We shall see how the Spanish crown’s attempt to oppose this historical trend will represent one of the causes of the war with Great Britain and the beginning of the national revolutions in Latin America.

Latin America at the end of the 18th century

From the point of view of social relations, we witness, especially in Mexico, the transformation of village communities into haciendas owned by the latifundists, who use peonage as a method of exploiting peasants. Since 1609, Indians are forced to work the lands of their conquerors, except that they can ‘freely’ choose the master they want. Subsequently, in a process very similar to that experienced by European peasants, the landowners indebt their own peasants with the aim of binding them to the hacienda. The owner advances the peons part of their wages and part of the operating capital in seeds to cultivate the small plots of land that the peasants need to survive. The peon could leave the hacienda on condition that he pay his debt, but this would never happen: the law stipulated that indebted Indians had to remain on the property. The large latifundists thus have absolute power over their boundless territories: they have the right to judge the peons and have militias to maintain order over the labourers and the villages.

The figure of the peon is similar to that of the poor peasant: indeed, he owns a small plot of land and is also forced to work for the landowner in order to survive and pay off the debt he has incurred. It could be argued that, in fact, the type of servitude that is created is similar to that between feudal lords and peasants in the Middle Ages, but this is not accurate in light of the economic categories: the relation of servitude is mediated by money and interest, that is, by the advance of capital to the small producer, albeit in a most rudimentary form.

This way of managing the haciendas is therefore entirely based on the capitalist mode of production, although one cannot fail to note that it is a backward form: both with respect to the large-scale management of farms through wage labour, and to the parcelled management of the latifundium through the division into small plots given in tenancy to free peasants. This is transitional form between a stage of slavery – such as the encomienda or the large tropical plantation – and the management of the countryside through the modern capitalist method with the labour of the agricultural wage-earner.