|

|||

|

Party meetings in Florence December 1975, March and October 1976 The Cycle of Accumulation and Catastrophe of World Capitalism (Il Partito Comunista, No. 21-29, 1976) |

|

- Simple accumulation and expanded accumulation - Production and consumption - The Marxist theory of the crisis in its terrible historical confirmation - Phenomenology of the capitalist economic cycle |

Communists pride themselves on possessing a more general, more realistic view of social phenomena than that of other parties; they do not limit their criticism to the currently implanted mode of production, but extend it to the historical succession of different ruling classes and the legal and productive relations they maintain.

Dialectical materialism, as a reflection in thought of the clash of social forces, is the form that the party’s consciousness of the historical becoming of the relations of these forces and tendencies takes, that which makes us recognise in the enemy’s overwhelming power its own death sentence and in the more peripheral, unconscious and uncertain rebellion of a few proletarians the force that can bring it down. The power of Marxism, in fact, to the discouragement of the host of priests, theorists, policemen and traitors hired by the regime, lies in its being based on reality: it has not criticised the wage system because it is unjust, inhuman and violent, but accused it of rising to infernal heights of injustice, inhumanity and violence because it was unproductive in relation to the needs of the species, and not in absolute terms but in relation to how much more efficient a different articulation of the already existing productive forces could be.

The more capitalism develops the productive forces, the more it revolutionises and disciplines labour energies, the more it subjects nature through science to the necessities of production, to the same extent it accumulates before itself the obstacles to be overcome for its preservation. Its ‘historical mission’ (the term is Marx’s and is to be understood in a material sense, what the order of things determined it to develop), its historically and socially useful aspect, its progress is precisely the cause of the narrowing of its possibilities for survival.

This contradiction immanent to the mode of production in every moment of the production cycle and in every elementary act of exchange, manifests itself in traumatic form in the mechanics of economic crises in which the imbalance accumulated in previous phases of productive expansion is concentrated. The distortions caused by the divergence of economic laws from the harmony of the laws of nature, as the early utopians would have expressed it, abruptly come to a collapse, the violent destructive crisis breaks through the repressed disequilibrium and allows the new linking of the laws of capital to the conditions of its market, the attainment of a new equilibrium but different from the previous one, permitted only by a further qualitative growth of the productive forces, the origin and end of a new cycle of accumulation.

The whole of Marx’s Capital, which at the meeting we did nothing more than re-present by reading some passages directly from it, in the power of its structure is a representation of capitalist hell faced with that scientific method that only revolutionary passion allows in social facts; round by round, from the chapters on the commodity to those on simple reproduction, down in a gigantic spiral that nonetheless converges in a single funnel: the increasingly violent crises, the progressive impossibility of accumulation, behind which the spectre of social revolution looms menacingly. That capitalism is a historical mode of production is the conclusion that flows from the gigantic work, a titanic slap in the face of all reformers. Reformers of the national-economy, despite your best efforts, it will die.

Capital does not describe capitalism in itself, but in its becoming, not what it is, but what it is transforming into: to draw the limits against which the present associated way of life – the forms of production – collides is nothing other than to outline the conditions of destruction from which the future order will free itself. If in capitalism exchange value is forced to coexist and finds a limit to its realisation in use value, in communism the contradiction is resolved in the ‘regulation of production according to a plan determined in advance’ and dissolves the equation, not mercantile but objective, between the needs to be satisfied and the socially necessary labour time required to satisfy them.

All revolutionary movements have possessed, well before their societies were established, a certain knowledge, positively, of the future social order for which they fought, perhaps in the form of mystical advents of divine kingdoms. Marxism has a negative one, it describes the infamous present and marks out what communism will not be, it knows what is necessarily transient in the present society, it warns of what the revolutionary movement will have to destroy rather than getting lost in the conjectures of what it purports to build. However, because of the method it wields, its prediction of the coming life of relations is incomparably more precise, closer to the possible than those of previous reformers as well as, of course, the bourgeoisie now blind and superstitious even about the present.

The report presented at the meeting aimed in particular to illustrate what in Marxism was the explanation of the causes and effects of periodic economic crises.

For the purposes of systematic exposition, Marx distinguishes simple reproduction from expanded reproduction. Only the latter is typical of capitalism. In earlier modes of production, the means of production, not yet capital, while producing surplus product, do not systematically accumulate. Primarily based on agricultural labour, the number and quality of implements grows slowly, and with them the productivity of labour; as long as the ratio of the number of mouths to feed, arms at work, and the land is abundant, there is no need to extend production faster than the birth rate; the breadth of production grows, not its intensity. Only a change in elements not immediately inherent to the sphere of production can threaten the preservation of such systems; a population increase in the late Middle Ages; an invasion of capitalist goods in Asia. At their core, these are static regimes. On the contrary, capitalism is a continuous transformation: motion is both its reason and its condition of existence, its ‘historical mission’ and its necessity. It generates within itself the material conditions of a new society, while it creates, concentrates and educates the class that will wrest power from it.

It is the regime of perpetual instability, a desperate race between, on the one hand, the concentration of the means of production in the form of capital; reinforced by ironclad state apparatuses of coercion and falsehood and, on the other hand, of the misery of ever more concentrated and threatening proletarian masses.

The production of guilds declines when the simultaneous use of different crafts becomes necessary and the collaboration of more workers becomes more important.

The technical necessity of concentrating men, means and knowledge in the same productive unit found, historically changed from the past, the form of individual ownership, of monetary accumulation; a general social necessity to assert itself and explode is compelled to anchor itself on the support of preexisting static and individual juridical forms; the capitalist builds railways, creates cities, in his eyes everything and only for the sake of profit. With the development of production and trade, with the concentration of factories, the figure of the owner vanishes into abstract anonymous collective entities, which remain, however, the owners of the value of the product, the profit.

But by now and increasingly so, knowledge no longer has any boundaries between one human group and another, the synthesis of different civilisations accelerates its progress; the search for new production techniques, for new properties of nature, in itself parallel and collective, instead takes on the character of competition, seemingly the only antagonistic connective tissue between men and nations, a struggle to grab and privatise social progress.

The natural selection among companies, however, can no longer be stopped: the irreversible creation of the world market makes a return to autarkic economies of the medieval or Asian type impossible, just as it renders the super-imperialistic perspective both impossible and reactionary. All corporations require the largest possible market to dispose of their excessive production, on that terrain survives the industry that produces at lower costs, that on a larger scale and with greater efficiency utilises natural forces and labour energies. The petty aim of perpetuating the accumulation of profit drives capitalism as a whole to revolutionise production processes ceaselessly and with it all aspects of social life.

The tendency to introduce new machines, and the more rational use of them, is a constant of capitalism; the number and value of machinery increases and the number of workers needed to operate it decreases, i.e. the organic composition of capital, the ratio of constant capital (raw materials and wear and tear on the means of production) to variable capital (wages), constantly increases.

At the same time, the amount of goods thrown onto the market increases.

From a general point of view, the effect of the evolution of capitalism therefore is:

1) Increase in labour productivity, with the same working day much more wealth is gradually produced, commodities become cheaper, while the share of work that the worker at the end of the day transfers unpaid to the capitalist also increases. This is the progressive component of capitalism, although today capital appropriates the surplus labour. That the worker needs less and less (necessary) labour time to reproduce his labour power, in absolute terms and as a fraction of the day, is an indispensable condition of any higher social order: the enormous mass of working time which, already today, exceeds what is necessary for the satisfaction of the elementary needs of the worker and his family, and which is used for the maintenance of the ranks of the idle bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie, as well as the insane accumulation, can tomorrow be directed, individual biological survival no longer being an impending necessity for the great mass of workers, towards all those more specifically human activities, at last free, both collective and individual, of thought and body, as the nature of man allows and therefore requires, in forms and measures that today are masked even by the prediction of the infamous bourgeois trade of ‘leisure’ and ‘recreation’.

2) Relative to the same magnitude of capital, the value produced (rate of profit) decreases. Indeed, as an ever-greater portion of capital is employed in means of production, which in the industrial process merely transfer their value unchanged to the product, and a smaller portion in living labour producing surplus value, although the productivity of labour increases, the productivity of capital decreases. It follows, therefore, that as capital evolves, it becomes sterile, less productive in generating surplus value and, therefore, in order to keep the mass of this surplus value constant or to increase it, capital is forced to expand more rapidly the total capital put into motion, i.e. to extend the production of commodities.

Capitalist production is always governed by the alternating outcome of the clash of these two tendencies: maximising the mass of profit while constantly decreasing its specific productivity.

The two tendencies also influence each other: a fall in the rate of profit induces manufacturers, on the one hand, to strengthen their individual position on the market by lowering their production costs, usually by further increasing the share of constant capital, and, on the other hand, to expand the scale of production in order to obtain the same mass of surplus value at a lower rate. But, as we can well see, as soon as the better technique, introduced as a reaction to the fall in the rate of profit, has spread among all producers, the advantage of producing at lower costs will become the norm, meaning a decrease in the value of the commodity produced and finally an inexorable further lowering of the rate of profit.

This mechanism, although in the real process it is complicated by counteracting phenomena that may even reverse the historical trend in the short term, summarises the infernal engine that perpetually contorts the international landscape of capitalism: nations that at different speeds rise to great power by concentrating production and trade on their territory, only to decline and cede dominance to others, continuous flow of capital from one region to another, from one industry to its competitor, continuous alternation of the rhythm of accumulation with the typical cyclical trend, always ending in a crisis, a halt in the capitalisation of the production mechanism.

It is evident that, since the reaction to the falling rate of profit does not have the effect of opposing, of slowing down the progress of this phenomenon, but rather of accelerating it, the system as a whole can never reach a condition of stable equilibrium, indeed it can be said that the only possible equilibrium for capital is accelerated motion, only in a continuous expansion of the scale and intensity of the extortion of unpaid labour does it find a compensation, a dynamic equilibrium between the contradictions that shake it. Many examples could be given of the various phenomena in capitalism that follow this inexorable demented trajectory, which can only dissolve at the breaking point, through catastrophe.

Are the markets flooded because too many goods have been produced? In a non-capitalist, pre- or post-bourgeois regime, society’s reaction would be to temporarily save labour energies or divert them to other activities until the balance between wealth and needs is restored.

In the current mode of production this is impossible, indeed disastrous. It seems so simple, so immediately comprehensible, so congenial to the nature of the relationship between human subsistence and the surrounding environment, yet to advance such a hypothesis is to be found neither the voice of an economist nor the programme of any party, from right-wingers to super-radical opportunists. Advocating such necessity at this juncture of counter-revolution today are a few communists clustered around our party core. And not by chance: this elementary measure is the death of capitalism, the gist of the revolution’s immediate economic programme: disinvest capital, dismantle useless production.

The terror, which like a death knell, such a proposal arouses in all defenders of order, national-communists foremost, stems from recognising in it the abyss into which the regime is plunging and the threat of the proletariat’s movement for that urgent necessity.

In capitalism, a flooding of the markets, and this is why it has been revolutionary, does not act as a brake on technological development, but as an accelerator: unit costs must be lowered, faster machines must be introduced, production must be increased; newly contested markets open up and are flooded with goods, until the phenomenon is reproduced on an even larger scale, involving more productive sectors, and all regions of the world.

The trouble for capitalism is that it cannot go backwards, it cannot scale itself down. Every new discovery, every ingenious improvement in production techniques cannot be erased, it becomes, in spite of itself, no longer the patrimony of the capitalists, but a perennial social endowment, and absurdly, it is precisely the unbridled competition between private individuals for private property that spreads and socialises discoveries and makes their general use irreversible. Obliged therefore, is capital, in contrast to the mental narrowness and cowardice typical of the individual bourgeois, to project itself eternally into the future, its course can only compensate for excessive expansion with further expansion, for excessive speed with acceleration, for an excess of constant capital with the purchase of, perhaps new, but still constant capital, overproduction with further production, for the underconsumption of the proletariat, which will never be able to consume all the goods produced, with further proletarianisation.

Capitalism, we have seen, is characterised by a continuous evolution of the quantity and intensity of its mode of production to which corresponds an opposite constancy of legal forms, of the relations of production in which society is hinged.

Marx, when speaking of the sale of labour-power, states: ‘The capital-relation during the process of production arises only because it is inherent in the act of circulation, in the different fundamental economic conditions in which buyer and seller confront each other, in their class relation’ (Capital, Vol.2, I.I).

Capitalism is defined as the relationship between men and the means of production, between the proletariat and the monopolisers of the means of production, first in the production process with the sale of labour-power, later in the distribution of the surplus product between the ruling classes and the distribution of wealth. In this sense: ‘The process of production therefore appears to be only an interruption of the process of circulation of capital-value’ (Vol.2, I.I.III). Hence also our thesis that the regime to be overthrown is entrenched outside the sphere of immediate production, outside the factories.

Similarly, the whole process periodically comes to a halt, not because of the emergence of technical difficulties relating to the ever more complex production processes, even if working in capitalist galleys is hellish for proletarians, but because of the non-responsiveness of this gigantic production to the quantity of proletarians offered on the market and to the possibility of the different classes to buy the means of subsistence produced. Despite the historically proven tendency of the fall in the rate of profit, the capital cycle, as far as the production process alone is concerned, could continue indefinitely. At the moment when production stops, the plants are, in fact, at their maximum efficiency and capacity and only ask to be put into motion. The same goes for the availability of capital. There is also too much capital, all that is needed is for it to be... invested (Invest it! suggests, triumphant over the tautology uncovered, the opportunist imbecility). But the rot is not there: theoretically, from a material point of view, at least until the raw materials and energy of the world’s proletarians are exhausted, it would be possible to go on in this demented orgy of production, so much so that in certain sectors of particular pestilence, production already runs up against the limits of the very laws of nature.

The immediate effect of the fall in the rate of profit is the expansion of the mass of capital, in the magnitude that history has shown, no social or natural measure being given; the illusion of capital is to produce for the sole purpose of producing. The rude awakening comes, when the mountains of unsold commodities vigorously protest that a self-respecting commodity (on the market) must, sooner or later, serve something other than production itself, that one only gets out of the capital cycle with the passport of use-value.

It should be noted that the utility of a commodity is not an absolute fact, although capitalism is constantly creating new and more extensive needs, even of the proletariat, the part of the income destined for individual consumption grows, (when it grows) in far less proportion to the mass of surplus value extracted. The disproportion thus arises between a monstrous wealth-producing machine (aside from our criticism of what and how it produces) and a mass of workers who are, and in capitalism will always be, inexorably separated from this wealth. By definition surplus value is transferred outside the proletariat. The depersonalisation of capital and knife-edge competition also limit the share of surplus value that industry can afford to distribute to the unproductive consumption of the ruling classes.

Opportunism complains to cronies about ‘cathedrals in the desert’ (there should be small rectories around where it would be easier to snatch a few alms). But the entire capitalist production machine is a ‘cathedral’ that has made a desert around itself, that subdues and centralises in itself all the lesser production units, concentrating in itself the means and the end of its movement.

When world overproduction has reached a certain level, it takes almost nothing, even an accidental event to trigger the crisis, an unexpected fluctuation in demand, a seasonal shift, and panic spreads suddenly among the agents of capital. Suddenly it is realised that the enormous mass of goods already produced cannot be sold at its value, that it has no value, that the gigantic plants will never be able to run at full capacity all at once. But it is only thanks to this illusion that capitalism has been able to proceed so far and still tries to push accumulation even when the first symptoms of overproduction have manifested themselves. This is the current situation. The first reaction of manufacturers is to hide their difficulties from their creditors, from the banks on whose credit they depend, to speed up production in order to lower unit costs and carve out a bit of market space.

Asked by the newspaper La Repubblica on 10 June about the current state of companies’ balance sheets, a stockbroker replied: ‘Very bad. Many companies spend 8-10% of their turnover to obtain the money they need. Under these conditions it is impossible for them to stay afloat. As long as they can do so, they will hide their colossal losses in the folds of their balance sheets, then they will collapse. And I am not talking about small and medium-sized enterprises, but about some of the largest companies in the country’. It is clear that these companies are not only already making below average profit, not only below the bank interest rate, but even negative profit if they want to enter the market. It is clear that it is only thanks to the intervention of financial credit that the situation is so dramatic, but also that it was precisely because of this intervention that it has been able to drag on for so long.

Indeed, by means of credit, not only is it possible to produce before and without the existence of buyers, but it also allows the use of means of production and materials before their equivalents exist, taken away from society in exchange only for the hope of continued insane capitalist expansion. One produces with capital whose value has not yet been produced, inventing capital, cheating at the game of ‘honest exchange’ which is too narrow, each capitalist trusting that he has completed his cycle before the scandal explodes. All the agents of capital thus have a common interest in releasing the brakes on the bandwagon as the slope turns into a precipice, nor, for that matter, could they stop it, even if they wanted to.

Credit is the ultimate and most perfected instrument of capitalism in its illusory tendency to emancipate itself from its own limitations, from mercantilism, from the exchange between equivalents.

It is, at the same time, the undoing of the liberal principle whereby the needs of the people would exert a severe selective action on capitalist trade by imposing that proportion between the various branches of production that responds to ‘demand’. Not only have terrible world crises – certainly cursed by all – erupted and had their epicentre precisely in the countries where this doctrine most rigorously informed trade legislation, but it has become evident that the hunger for surplus value has dictated even over the nature of ‘demand’, considered sovereign, modelling it according to its extravagant needs.

By transferring capital from one branch to another according to the evolutions of the particular rate of profit, credit is responsible for making the crisis occur simultaneously in all spheres of production and in all countries. It is no longer a question, as may happen, of overproduction of a particular commodity but overproduction of commodities, i.e. of capital – commodities that cannot continue their metamorphosis. It is the overproduction of capital.

Given the particular market conditions, the disproportion between the mass of capital and the restricted scale of reproduction suddenly becomes apparent. Only a part of the existing capital can continue to produce surplus value, while an addition of new capital would have the effect, by causing prices to fall, of reducing the mass of surplus value instead of increasing it. The conjuncture for capitalism has no way out, squeezed on the one hand by the lower productivity of capital, on the other by the need to contract the scale of production. The effects can only be: dramatic fall in the rate of profit and partial destruction of idle capital.

Destruction of means of production by simply remaining unused or at least suspension in their form as capital.

Bonds, shares and in general securities owned on shares of future surplus value lose their market price to the extent that such future income loses its certainty.

The capital that is in the phase of commodity-capital, if one wants to transform it into money-capital, one has to exchange it at a price that is only a small part of the real price of production: capitalism, in the period preceding the crisis, absorbed an amount of labour time beyond the ‘socially necessary’; in the crisis, the proportion is violently restored by exchanging the mass of overabundant commodities only for the equivalent of the ‘socially necessary’.

Capital in the form of money, whether gold or silver, simply ceases to circulate as capital, to exchange for means of production and labour-power, and becomes fixed as a store of value. But hard currency notes, commercial securities find their measure in the guarantee of their operation, in circulation itself. The chain of payments is broken by the insolvency of capitalists and merchants. With the loss of value of commodities, the value of the credit securities secured on these commodities also vanishes. Capitalism suddenly realises the gigantic international bluff it has been mounting with the sweat of millions and millions of proletarians for years.

As the regime evolved, the national and global structures specialised in delaying the moment of crisis both economically and socially, in tossing the bombshell across borders. There has been no shortage of imperialist success, so much so that, at the cost of the bestial oppression of huge masses of proletarians and semi-proletarians, the periods between crises, as Engels already noted, have been prolonged, but all the more terrible have they become in this century, to the point of taking on the appearance of veritable global catastrophes of the capitalist regime. The mass of excess capital is of such monstrous dimensions that only a specific and organised destructive intervention, concerted among all states, can restore the balance. Only in capitalism are wars so immediately a means of production, integrated into its now semi-secular cycle.

The economic crisis unfortunately, with the destruction it entails, does not in itself mark the end of capitalism. The doctrine teaches and history has demonstrated that the crisis, the culmination and collapse after an abnormal period of productive euphoria, is also the material premise for adjusting the conditions of production, the market and the availability of labour-power, to begin a new cycle with a lowered rate of profit, adjusted to the modernised productive structures.

Marx in the third section of the third book, which he personally completed, where he considers the law of the fall in the rate of profit with its contradictions i.e., the infamous heart of capitalism, warns that: ‘The ensuing stagnation of production would have prepared – within capitalistic limits – a subsequent expansion of production. And thus the cycle would run its course anew. Part of the capital, depreciated by its functional stagnation, would recover its old value. For the rest, the same vicious circle would be described once more under expanded conditions of production, with an expanded market and increased productive forces’. The emphasis is ours.

The most significant example is that of the 1929 crisis, which dragged on with alternating phases and found its international solution in war. Today the cycle that began then is coming to an end and the expected economic upheavals are of similar depth.

But the false Marxist and communist parties that lead the working masses have descended below the social-democratic doctrine of progressive and peaceful development. Faced with the evident crisis, of which, until yesterday, they even denied a return, they pretend to make Marxist economic theory available to the bourgeoisie for the opposite purpose to the one for which it was born, they want to ‘get the country out of the crisis’. We know that world capitalism will indeed come out of its terrible periodic crisis, but with immense destruction, by starving the proletariat.

The petty bourgeoisie terrifies itself, curses technical development, the international exchange of knowledge, expresses apocalyptic predictions in which its ruin as the courtesan of capital is taken as the very end of civilisation. It implores capital to put the brakes on its course. Actually, it would like to put the brakes on everything: put the brakes on consumption and stop the birth rate, because otherwise there would be too many of us and we would risk eating less; put the brakes on production, but not on the income that comes from it; put the brakes on the excess of freedom together with the excess of authority; in short, it envisages a ‘coming Middle Ages’ made up of many bunkers where, with the world market abolished by law and a reserve of corned beef, it can wait, huddled in the warmth of its home, for the atomic hailstorm between the imperialist giants to pass.

To the proletariat, of course, such a prospect is precluded by circumstances (and also to the petty bourgeoisie itself of course). At the present stage, capitalism is trying to delay the explosion of the crisis, the blockage of production, the vertical collapse of prices and the emergence of millions upon millions of unemployed. International agreements between bourgeois states, divided on everything else, agree to reduce the share of capital allocated to wages for the same amount of labour time absorbed, while, as we discuss elsewhere in this issue of the paper, the traitorous trade unions are in the front row to make their fifth-column contribution.

It is up to the proletariat to respond from now on, on the economic terrain, blow for blow, because to give up today ‘because there is a crisis’ would constitute a serious lien on the movement, when, having closed the factories at the height of the collapse or at its conclusion, it will be a matter of defending the very life of the proletariat against the political apparatus and the international military discipline of capital, to disarm its guardians once and for all.

* * *

The first was the pound that devalued in 1967: this time it is the franc that will mark another significant step in the economic decline of the old imperialist powers. And just as then, standing above the already waning British and French imperialisms are the more dynamic or more extensive powers, the American and the German, which in reality are colliding. The upheavals that the flow of dollars are now constantly causing in London, Paris and Rome are increasingly tending to become mere episodes, clashes in the periphery of the struggle for the imperialist survival of the United States against the resurgent West Germany. The real objective of the Americans in the immediate term is to force the revaluation of the Mark. The German-American confrontation is the necessary result, foreseen by the party, of this post-war capitalist development: during the twenty years in which the Japanese and German powers rebuilt themselves with impressive speed, US imperialism ruled by robbing all over the world. Since 1967, therefore, capitalism has entered the phase in which the symptoms of the expected crisis of overproduction would manifest themselves, the objective premise of the historical and worldwide proletarian boot to kick away all the rottenness of today.

Monetary crises have been occurring continuously ever since, regularly wiping out the various inter-state agreements, whether tariff, trade or monetary (most recently the ‘snake’ that the Germans, already their prime guarantors, are forced to drop as a useless burden in the storm). Woe to the weak, when it goes wrong every ‘national economy’ looks to save itself by drowning its brothers.

The rise in oil prices at the end of 1973 causes a strong drain of surplus value from countries lacking it. The resulting inflationary pressure and sharp fall in the rate of profit destabilise and exacerbate international competition to the advantage of the US which controls the world currency.

After two years of international crisis, the contrast between temporary winners and losers is clear. The measure of the gap is marked by colossal balance of payments deficits or surpluses. In 1976, in addition to the oil-producing countries, only the United States, the Federal Republic of Germany, Japan, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Belgium would close the year with a surplus; all the other industrialised countries would, on the whole, run up deficits of 11 billion dollars; the non-industrialised countries with a deficit of 43 billion. These deficits are therefore covered by loans from the big three, namely from American banks that gain control of the money market; Italy, for example, now owes 16 billion dollars from abroad, France 18 billion.

In this post-war period of fetid prosperity, after the not insignificant crisis at a ten-year pace in the USA in 1958, where in 10 months industrial production plummeted by 15%, the first industrialised country to report a production recession was, not by chance, precisely West Germany in 1967, where, from November ‘66 to the following August, production plummeted by 19%. France, Great Britain and the USA merely slowed their growth. Two years of recovery followed and then came the recession of 1970-71, most severe in America, but almost the whole world suffers. There, a decline of 4% between 1969 and 1970.

Two more years of productive momentum followed, almost a boom in 1973. This is the sign of the unleashing of inflation at an unprecedented rate: wholesale prices rose in the USA by 14% in 1973 and 19% in 1974, in Italy by 18% and 41% (!), in Japan 16% and 31% (!). One has to go back to the war years to find higher ones. The inflationary phenomenon continued apace despite the sharp recession of 1974-75.

In fact, even this time the productive momentum was short-lived: the first country to interrupt the recovery was the United States in September 1973, in November Germany, Great Britain and France; Japanese industry continued to expand until March, while Italian industry held up until the following October.

The recession hit all countries in the western world, including, finally confirming the long-anticipated historical proof, the social democratic paradise of Sweden and wealthy Switzerland. The bottom of the recession is reached in July-August 1975. Considerable ground was lost: 9% drop in production in America and calculated between the annual averages of ‘74 and ‘75; -10% in Italy; -5% in Great Britain; -11% in Japan; -5% in the FRG. These are still not ‘1929-type’ rates, roughly half (and only a single year decline) but by far the worst since. Correspondingly high is the officially recognised number of unemployed, which at the beginning of 1976 reaches one million in France, two million in Italy, 1.4 million in the Federal Republic, one million in Japan, 1.4 in England, 8 in the USA.

Future necessary studies by the party on the evolution of the crisis will deal with money and capital flows. Here we provide a table of the percentage increases in industrial production that highlights the latest short cycles of world capitalism. Marked in bold are increases indicating recession or stagnation. The data come from traditionally party-curated statistical overviews and UN bulletins.

| Great Britain |

U.S.A. | Germa-ny | Japan | France | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 7.0 | 2.0 |

| 1965 | 3.7 | 8.5 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 4.9 |

| 1966 | 0.9 | 9.6 | 1.8 | 13.3 | 6.4 | 11.2 |

| 1967 | 0.9 | 0.8 | -1.8 | 19.1 | 3.4 | 7.6 |

| 1968 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 12.3 | 17.3 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

| 1969 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 12.5 | 16.8 | 13.6 | 2.9 |

| 1970 | 0.0 | -3.8 | 6.6 | 13.6 | 6.4 | 6.8 |

| 1971 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 |

| 1972 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 3.9 |

| 1973 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 6.7 | 15.5 | 7.1 | 9.6 |

| 1974 | -3.5 | -0.9 | -1.8 | -2.4 | 2.5 | 5.2 |

| 1975 | -4.7 | -8.6 | -5.4 | -11.3 | ... | -10.0 |

| 1976 Feb | 0.9 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 12.7 | ... | 3.6 |

It would seem to follow an alternating rhythm of just over four years, as the crisis years were in fact: 1966-67; 1970-71; 1974-75. If we limit ourselves to mechanically extrapolating this period backwards we can observe how almost all the crises or productive stagnations of this post-war period fall ‘in phase’: 1948-49 recession in victorious America; 1952-53 crisis in Great Britain and France, only stagnation in defeated Italy and Germany; 1957-58 (this time the period is five years) crisis in the USA and Great Britain, slowdown in the Federal Republic and Japan; 1961-62 stagnation again in the USA and Great Britain. Thereafter, in cadence, the three major international crises outlined above.

Not lacking at this point was the gigantic US research institute which, in honour of the empirical method so dear to the Anglo-Saxon bourgeoisie, extrapolated forward instead: 1974 plus 4 and you would arrive more or less at 1978.

One fact is certain: not even the bourgeoisie dares any longer merely to hope for a future of flat and progressive economic and thus social development: the 1975 crisis, though deep, was too short-lived to resolve the contradictions accumulated over thirty years of frenzied production all over the world. Faced with the immense mass of unsaleable goods already produced, capitalism now needs far more drastic destruction in order to regain momentum. In imperialism, crises are worsening and extending, as we know from our theory, from past experience, and as is confirmed by the growth in depth and generalisation of the last three crises.

The same international mechanism of imperialist domination with state control over currencies has repeatedly been able to delay the explosion for the time being by offloading the necessity of the production and market contraction onto the economically weaker countries. But it has only exacerbated the phenomenon and not for long. After the recession that culminated in 1975, the current upswing in production tends to bring to the surface only the most pestilential capitalisms, and manifests itself in such stunted and deformed forms as to rule out the possibility that it is the beginning of a new economic cycle in which the market returns to a new expansion: on the contrary, everything points to an ephemeral surge. In America the overall economic expansion was 9.2% in the first quarter of the year but only 4.4% in the second. The unemployed were 7.5 per cent of the labour force in June and a tenth more in July. In Germany, despite the recovery, unemployment remained high and emigrants were being repatriated.

In all the other countries, central bank interest rates are very high: 9% in Belgium, 9.75% in France, 11.5% in Great Britain, even more in Italy, meaning that this recovery is not the result of new capital investments (and thankfully so! though opportunism mourns...) and that widespread replacement of the exhausted fixed capital across the entire productive surface as at the beginning of every new period of accumulation is not taking place. On the contrary, even existing plants are not fully utilised, and the unemployed fuel the informal economy while factories are closed.

The huge balance of payments deficits of the less wealthy countries are the limit against which the exports of the more prosperous ones bump, and the new monetary adjustments and the failure of the European agreements will tighten the commercial noose around West Germany even further. This country is a concentrate of the contradictions of the most rotten capitalism: with a balance of payments in surplus for more than twenty-five years it overflows with capital, but cannot afford to increase consumption (horror!) threatened as it is by diabolical inflation, unemployment at 6% of the workforce, and it is the richest country in the world, envied by foreign bourgeoisies and opportunists alike.

Germany, even while halved, is already too cramped to contain its infernal capital. The terrible unknown of history is: will the resurgence of proletarian movement in the heart of Europe precede the military resolution of the world capitalist crisis? Some explosions of wonderful class anger seem to herald this.

The report on the economic crises of capitalism first concluded the brief exposition of the theoretical positions of our doctrine, already begun in previous reports using the specific chapter of Marx’s Theories of Surplus Value. In the text, after identifying in the movement of money the form in which the two antithetical moments of bourgeois society, social production and appropriation of wealth, are separated and then violently reunited, it is revealed that this formal, potential possibility of crisis finds its real manifestation and immediate determinations in the development of the typical categories of capitalism: competition and credit. While the possibility of crises is already contained in the abstract in every mercantile economy, only in capitalism, and particularly in its highest form, imperialism, do they become real, cataclysms that periodically overwhelm the entire world.

The immediate explanation for the alternations of the industrial cycle, Marx states, must therefore be sought in the typical phenomena of modern capital reproduction, phenomena that only unfold their power in expanded reproduction and when different capitals already compete on the market.

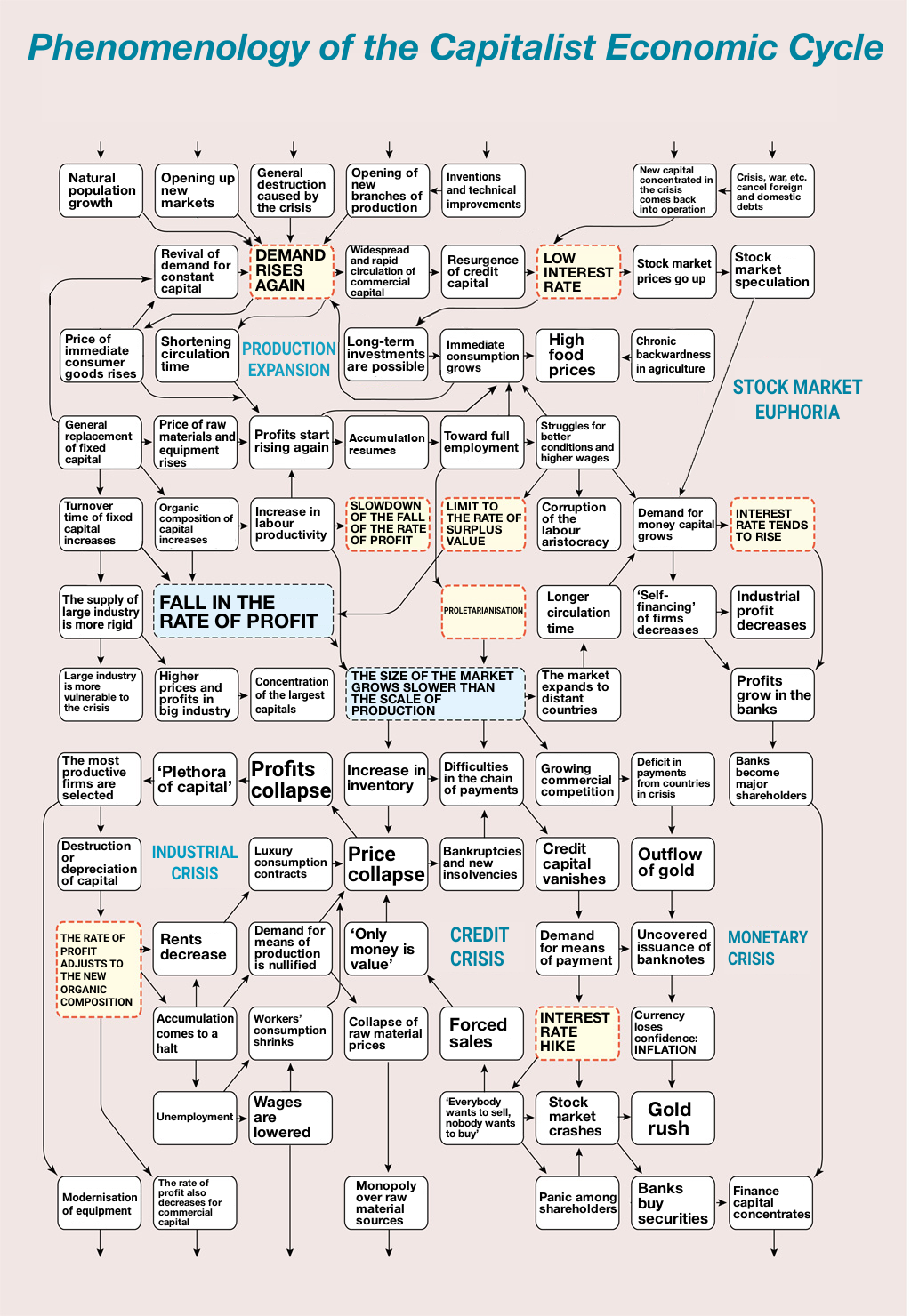

In order to illustrate to the comrades the complex concatenation of the many determinations that Marx already identified in the changing progress of the industrial cycle, a chart was then prepared in which the network of relative influences of the individual phenomena of reproduction, trade and credit were indicated with blocks connected by arrows. Each block indicated a specific event or reversal of a trend, while the arrows represented the direction of the cause-and-effect at that particular moment in the cycle.

As a first use of the schema in the research for empirical verification of the validity of our interpretation of the infamous bourgeois categories, graphs representing the values actually assumed by the official discount rate, the interest rate and the inflation rate throughout this post-war period, for certain countries, were finally presented to the meeting, showing their alignment with the predictions of the doctrine.

* * *

In Marx’s Capital, the study of the phenomena of economic crises does not appear collected in a specific chapter. However, throughout the exposition of both the Process of Production and of Circulation, as well as the Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole, anticipations of those particular contradictory aspects of the mode of production where material forces and inexorably divergent tendencies collide, which appear as the ultimate result already from the description of the elementary structures of the economy, are frequent, as we have already seen. We have quickly reviewed in previous reports these glimpses of the catastrophe of the most raging, even against itself, exploitative regime in history. Never does the possibility, the objective maturity and the historical necessity of production conducted according to a common plan, of the harmony of communist society fail to appear in these passages – where the reversal of capital’s progressive potential into its opposite, its destruction, is most manifest.

Marx failed to give his work a formally complete structure, he left the proletarian fighters with only the gigantic foundations of the investigation of capitalist economic categories. Already these, however, were enough to disprove and overcome the schools of classical bourgeois economics, while today the ruling class is precluded even from entering the theoretical battle with Marxism: theory is an impossible luxury for a regime condemned to death, only immediatist empiricism is useful for the survival of the whirlwind of crisis.

Written with the intention of applying the results of the investigation of the elementary forms of the commodity, of surplus value in its origin and distribution, and of capital in its movement, we are left with a large number of notes. Among these, a chapter collected in Theories of Surplus Value is entitled Crises.

Briefly here Marx re-examines the causes of crises in schematic form. He points out how the bourgeois economist Ricardo, terrified by the ultimate results of his own research into economics, which would lead him to the conclusion of the historical character of capitalism, forgot, in his description of the crisis, that he was dealing with not only capitalist production of commodities but also commodity production when he argues: ‘[The producer,] [b]y producing, then, he necessarily becomes either the consumer of his own goods, or the purchaser and consumer of the goods of some person’. Marx at this point is forced to abandon classical bourgeois economics: ‘This is the childish babble of a Say, but it is not worthy of Ricardo,’ he remarks, ‘[N]o capitalist produces in order to consume his product (…) Now even the social division of labour is forgotten (…) A man who has produced, does not have the choice of selling or not selling. He must sell. In the crisis there arises the very situation in which he cannot sell…’.

In capitalist production as a whole, the necessary succession of the process of production and the process of circulation of the single elemental commodity, merely represents, on a gigantic, social, now global scale, the separation of buying and selling as well as between its characteristics as a commodity produced and commodity consumed.

From the very first section of Volume One, the one on Commodities and Money, the analysis already of the elementary form of wealth in mercantile societies, the fetish that embodies the economic relations between men, carries within itself, in its circulation, the germ of all the contradictions that arise in the movement of commodities as a whole: ‘If the interval in time between the two complementary phases of the complete metamorphosis of a commodity become too great, if the split between the sale and the purchase become too pronounced, the intimate connexion between them, their oneness, asserts itself by producing – a crisis. The antithesis, use-value and value; the contradictions that private labour is bound to manifest itself as direct social labour, that a particularised concrete kind of labour has to pass for abstract human labour; the contradiction between the personification of objects and the representation of persons by things; all these antitheses and contradictions, which are immanent in commodities, assert themselves, and develop their modes of motion, in the antithetical phases of the metamorphosis of a commodity. These modes therefore imply the possibility, and no more than the possibility, of crises. The conversion of this mere possibility into a reality is the result of a long series of relations, that, from our present standpoint of simple circulation, have as yet no existence’ (I, 3, 2A).

For those who know how to read, here is already contained the criticism of the de facto inadequacy of capital to satisfy human needs, the condemnation of the division of society into classes, because today ‘the representation of persons by things’ is called wage labour. And it will take more than calls for economic recovery from the croaking Berlinguer. Here are classes that have been clashing all over the world for more than a century, two opposing modes of production and thus of life: between the two lies not the reforms of red priests hired by the state but the violent destruction of bourgeois power.

Marx points out, this possibility of crisis is inherent in the mercantile form of the social exchange of wealth produced by the division of labour. The extent of this opposition, however, is not defined by this division, just as the form in which this division is resolved is not indicated. For as long as, although the technical division of labour is established, production tends predominantly towards immediate exchange, as long as it is produced for the purpose of consumption, the separation of the two acts occurs only accidentally, due to natural events, e.g. an exceptional harvest. ‘In a situation where men produce for themselves, there are indeed no crises, but neither is there capitalist production’. So, incidentally, in the stage following capitalist production or consumerism, when men go back to producing for themselves, there will be no such crisis.

But these notes by Marx are not just meant to be a summary of his past work but rather a trace, a powerful indication of the directions in which to push the investigation for a better understanding of the movement of capital as it is comprehensible in the light of its elementary structure. Referring to the overall circulation of capital it is said: ‘The general possibility of crisis is the formal metamorphosis of capital itself, the separation, in time and space, of purchase and sale. But this is never the cause of the crisis. For it is nothing but the most general form of crisis, i.e., the crisis itself in its most generalised expression. But it cannot be said that the abstract form of crisis is the cause of crisis. If one asks what its cause is, one wants to know why its abstract form, the form of its possibility, turns from possibility into actuality’.

Research must therefore aim to explain the alternations of the industrial cycle, which, as the capitalist system withers, turn into semi-secular periodicities in which all the contradictions of the bourgeois economy are concentrated.

All of Marx’s work on economics converges on the theory of crises, the death of capital, and the impossibility of its reproduction with the revolt of the proletariat, marshalled by capital itself.

The objectivity and accuracy of the powerful investigation of the bourgeoisie’s categories is historically destined to spring from their enemy, the proletariat, from an interested and biased position, the only one that can embrace in its science the entire course of the development of the productive forces from the form of the capitalist monopoly of the means of production, to their liberation from the shackles of the prevailing legal relations, to the overcoming and violent end of the proprietary and nominal forms and the eruption of the anonymous potentialities of collective life.

Marxism’s answer to the problem is general and not relative to a simple partial mechanism of production that is jammed: whatever accidental cause may trigger the destructive precipitation, the prime motive is thus stated in the notes:

‘[A] cumulative development of productive powers requires a constantly expanding market and that production expands more rapidly than the market, then one would merely have used different terms to express the phenomenon which has to be explained – concrete terms instead of abstract terms. The market expands more slowly than production; or in the cycle through which capital passes during its reproduction – a cycle in which it is not simply reproduced but reproduced on an extended scale, in which it describes not a circle but a spiral – there comes a moment at which the market manifests itself as too narrow for production. This occurs at the end of the cycle’.

This result that our class science was able to arrive at could not suffice. Later comrades embarked on the work of investigating the expanded reproduction of capital, research pushed just in the direction indicated here.

For now, the tragic repeated historical confirmation of the enemy’s vulnerability and, in the face of today’s terrible crisis at the gates, the pussyfooting around of the preening theorists of eternal prosperity, à la Marcuse and Co., is more than enough for us. What we are interested in investigating is the actual unfolding of the crisis, with its intertwining of economic determinations and social reactions. Marx indicates the mode of research in his notes with these words: ‘The individual factors, which are condensed in these crises, must therefore emerge and must be described in each sphere of the bourgeois economy and the further we advance in our examination of the latter, the more aspects of this conflict must be traced on the one hand, and on the other hand it must be shown that its more abstract forms are recurring and are contained in the more concrete forms’.

– Most abstract essence of crises: antagonism between the dual content of the elemental commodity in its metamorphosis.Capitalist categories are introduced, commodities appear on the market as the form of the metamorphosis of capital. The antagonism of the commodity is now the C-M-C antagonism, the commodities produced must not only be able to satisfy the demand for consumption, but also be capable of being transformed back into capital, in the quantity and quality required by the changing scale of reproduction. No longer is the individual artisan set against the individual consumer, but masses of capital employed in a given branch of production are contrasted with other capital differently employed.

Less abstractly: antagonism is mediated with money and is temporarily deferred with the further development of capital credit. And this form is already concrete enough to be able to explain the commercial crises resulting from the interconnectedness of the chain of payments.

For further elaboration, Marx says: ‘the real crisis can only be deduced from the real movement of capitalist production, competition and credit’.

The latter are the ‘new determinations’, the ‘more concrete forms’ of crises, particularly in the phase of the domination of finance capital.

It is impossible to disregard the competition among the gigantic capital concentrations for the division of the market. The constant fluctuations in international exchange rates are merely a consequence of this. It is in this sense that the research and interpretation of data representing the empirical course of the capital world must proceed.

* * *

The pendulum is the most common example that nature offers us of periodic motion. From the suspended mass, periodic variations of position, velocity and acceleration are observed. The rise and fall of the different quantities for some is concordant, for others not. When the height of the suspended mass is minimum, its acceleration is also minimum, but its velocity is maximum; when the suspended mass reaches its maximum height, the velocity, on the other hand, is nullified, but the acceleration is maximum. It is impossible to establish absolutely where the cause and where the effect lie: when the mass lowers, it is the altitude that generates the velocity; when it rises to the other side, it is the velocity that transforms into altitude.

One might wonder what triggered the phenomenon – the initial push – but even in the absence of an answer, it is possible to study it as it manifests itself in its repetition. Having written down the dynamic equations of the pendulum, we can predict its position at a future instant and also the phenomena that would occur if an obstacle were to stand in the way of the periods or else.

There are now almost 140 years of economic history in which the occurrence of periodic alternations in the capitalist economy as a whole has been established. Bourgeois economists have collected an immense mass of data and from this they have derived various empirical laws. Just as someone who, without knowing the relationship that exists in nature between force and acceleration, sets out to record the times and positions of a suspended mass cannot be excluded from finding the most probable future motion of a pendulum, without however predicting its behaviour in an external situation that is only slightly different, so all these ‘econometric’ attempts may also contain some truth.

However, it is certain that, just as a million empirical observations of the force-velocity pair are certainly not worth the third equation of dynamics (which, moreover, can never be verified in earthly experience), so far beyond the reach of any bourgeois science are our general theorems on capitalist economics.

Some of these theories are reported in Problèmes Economique of 6 October. There is one, called Short Cycles, according to which the period of fluctuation lasts about four and a half years, two and a half of which are economic development phases and two of which are recessions. We had already reported in our work on the crisis (see Il Partito Comunista No. 25) the existence of such a period in world production. Periodicities of around eight years have also been observed, but the observation that certainly comes closest to Marxism’s greatest historical prediction is the other said by Kondratiev who, perhaps without any sympathy for Trotski or the Left, discovered a periodicity of 50 years between the great depressions that hit capitalism: 1873, 1929 and 1975.

There is therefore a wealth of observations available to be used by the party, which alone holds the key to interpreting them fully, i.e. in their revolutionary content.

Before tackling the analysis of the course of the latest capital cycles as represented by statistics, a schematic representation, similar to the one we have given of the pendulum mode, of the succession of phenomena occurring during industrial cycles and the causal relationships was presented at the meeting.

The descriptions of the phenomena within the cycle as given by Marx in several pages of Capital and partly taken up by Hilferding in the chapter on crises are collected here, represented in graph form.

Each individual box represents an event (e.g. ‘Forced Sales’), or a trend (‘Proletarianisation’); the arrows indicate the direction of the relationship, from cause to effect, as determined at that particular point in the cycle.

From top to bottom the flow of time: at the top the typical phenomena of the beginning of a new cycle, the resumption of accumulation, then, descending, the phase of productive euphoria, then the collapse of the crisis and, at the bottom, the stagnation that succeeds it.

As a rule, therefore, the direction of the cause-effect arrows is from top to bottom or, at most, horizontal.

In a transversal sense, on the other hand, an attempt has been made to divide, for the sake of exposition, the phenomena relating to the spheres of production in the centre of the graph, those of the market and generally of distribution and consumption on the left, and those of finance and the capital market on the right. This obviously does not detract from the fact that numerous arrows cross the non-existent border between the three ‘zones’. On the contrary, we immediately notice how the crisis is determined precisely by these cross-determinations.

The chart begins (being a cycle it could begin at any point) in the aftermath of a general crisis: the main effect of this is indicated in the box: ‘General destruction caused by the crisis’. Other elements that characterise this particular moment in which capitalism, after having ravaged and plundered the entire world, presents itself to the tormented masses as rejuvenated, ‘reconstructing’ and ‘democratised’, include the reopening of markets already saturated or reserved for previous monopolies. Moreover, during the crisis, new technical inventions were set aside, now new branches were open up to capitalist production or those not yet invaded by modern machinery. The demand for the means of subsistence, although reduced, never ceases, as population growth immediately resumes, it appears in ‘Demand rises again’, at this time necessarily for basic necessities.

Four arrows emerge from this box: three on the left towards the commodity market, one on the right towards the money market. One determines, in view of the fact that ‘the production of raw materials is by its nature slow to adjust to demand’, an ‘rise in raw material prices’. The other determines the ‘immediate growth in the prices of consumer goods’. Remember – we will see this at the end of the cycle – that commodity prices start from levels far below their values, despite the fact that this phenomenon may be masked by galloping inflation.

For reasons of space, we must postpone the statistical demonstration of the phenomena that we are merely stating here.

The revived demand allows capital to resume its circulation more rapidly. The peace (we refer to the example of the post-war conjuncture), the renewed certainty of capitalists in their state and investments allows the issuing and circulation of credit capital to begin again. Compared to the moment of the crisis when the means of payment disappear from the market, this makes capital at this moment appear abundant, treasuries and commodities held idle during the crisis suddenly turn into money capital yearning to be transformed into productive capital, while at the same time the demand for credit is still very limited due to the overall constraint on production and the renewed confidence in credit among merchants and capitalists. Thus, the interest rate is always low at the beginning of the cycle.

At the meeting, a graph representing the development of the official discount rate for some major countries over even a century was shown, invariably verifying the phenomenon.

On the level of international relations, the crisis has involved the cancellation of the burden of debts and their enormous related interest with outright bankruptcies of individual national economies in relation to the winners. The devaluations are of such magnitude that national currencies completely lose all value. Just as, with the development of finance, concentrations no longer tend to drive the less productive enterprises out of the market but prefer to subjugate them to aggregate them into their power, so too, under imperialism the vanquished are not drained by reparations, they are literally invaded by goods and capital from the victor country, at this stage lent at low interest rates.

These are all preconditions for an ‘Expansion’ phase. This is brought about by the initial recovery of demand, by rising prices which, by their very tendency to rise, make it possible to counteract the fall in the rate of profit.

At this point in the cycle, the disproportion between low demand and even lower production is particularly noticeable: there is underproduction and underconsumption even though industrial demand is at an absolute minimum. This explains the high inflation values in the first years of the cycle.

It is, however, typical of capitalism to combine a disgusting chronic underproduction of consumer goods that condemns working humanity to a life of hardship, with a simultaneous underproduction of means of production relative to what would be the needs of capital accumulation: in the ascending phases of the cycle, due to the unnatural euphoria and the sudden manner in which it manifests, there is always an unsatisfied demand for means of production. When it concerns raw materials, that rising demand pushes towards the use of less fertile land and mines, causing a tendency for prices to rise (oil) and inducing capital to seek to forcibly transfer rents to itself (imperialism). When, on the other hand, it generates a demand that cannot be met immediately for means of production (since the delivery times for plants are always long) it causes temporary price increases and superprofits in the specialised branches of machine production.

Marx already noted that the replacement of fixed capital, in particular, with the development of increasingly gigantic machinery, does not take place evenly throughout the industrial cycle (and it is no coincidence that he called it that). The replacement of fixed capital embedded in large plants, chemical, steel etc. is concentrated at the time of the general renewal of existing technical capital, at the beginning of the cycle when masses of unused capital are available at low interest rates, which is necessary given the very long duration of depreciation. The technical possibilities exist because of the past accumulation of discoveries and inventions, and the economic possibilities because it is only at this point in the cycle that ‘new horizons’ of market dominance open up for capital.

The ‘reconstruction’ marches on at full speed: it is the time of major public works, steel centres, construction, motorways. The widespread expansion of these productions has, in the chart, two exits: one ‘Turnover of fixed capital increases’ given its gigantic size, and ‘Organic composition of capital increases’. These two trends converge in the ‘Fall in the rate of profit’. This tendency coexists in the chart with its opposite, as already seen, ‘Obstacle to the fall in the rate of profit’ otherwise determined. At this stage of the cycle, with the help of the constant rise in prices, these two tendencies may even offset each other.

Another arrow comes out of the magnification of constant capital ‘Increasing supply rigidities’ in the sense that the more a capital can only produce with increasing immobilisations of fixed capital, the more productive it will be, but at the same time the more it will be forced into a determined scale of production. As long as production allows, it survives over small-scale production and domestic industry, but it is much more difficult for it to adapt supply to declining demand in times of crisis. However, this phenomenon is favourable to it when demand for the products of big industry is on the rise: it temporarily results in a monopoly situation whereby ‘Higher prices and profits in big industry’ at this moment.

We have entered the realm of productive ‘Expansion’. Once triggered, the process is self-perpetuating without measure or social and human limits. The set of phenomena among which the effects in turn result as causes is graphically represented by a closed path with arrows all in the same direction: the growth of the individual magnitudes reinforces one other and the process would accelerate indefinitely if at the same time a condition external to the cycle did not alter and intervene to block even one of its steps.

The ‘Expansion’ cycle is represented here, without any claim to absolute completeness in detail.

The confidence of capitalists in being able to happily complete the production cycle, as well as their hunger for surplus value, drives them to expand the scale of accumulation: demand grows accordingly; 1) for raw materials; 2) for machines; 3) for labour power. The increase in demand and prices in the sector producing means of production leads to considerable expansion. All capitalist production in its mad rush appears to be constantly lagging behind, projected into a bleak future, competing between the various national concentrations. On the whole the mass of profit swells, not least because, due to the introduction of faster machines and the ease of trade, the number of rotations of the same capital in the year increases. This is despite the fact that the rate of profit decreases as constant capital increases.

Of the higher profits, a portion goes to increase the income of the non-working classes, another portion (the first closure of the cycle onto itself) goes back to expanding the very accumulation of which it was a product. The expansion of production of both consumer goods and means of production progressively reabsorbs all the available part of the industrial reserve army (this was only fully achieved in Italy in the mid-1960s). Competition among the exploited progressively decreases, defensive struggles allows for a temporary but noticeable growth in wages above the subsistence minimum for certain layers of workers: together with the consumption of the rich classes, the consumption of the proletariat also grows.

But the expanded sale of the industry’s final products, also due to the continuous upward pressure on prices that is made possible, is in turn both a condition and stimulus for the expansion of production.

Soon, as the rate of profit contracts, the money supply, set aside during the crisis, is no longer sufficient to feed a production that had expanded and was obliged, if it wanted to get ahead of its competitors, to anticipate and outpace demand (especially in the production of machines). Recourse to credit is indispensable, to an increasing extent as the cycle progresses. In fact, both due to the upward pressure on prices and to force demand from those who do not have cash, commercial credit swells. On the other hand, the necessary insufficiency or saturation of the domestic market pushes trade further and further away, prolonging the circulation time of capital and thus the total amount of capital immobilised.

When the interest rate is low, the demand for securities on the stock exchange increases; at the beginning of the cycle, when hopes for long and substantial incomes are particularly well-founded, stock prices are at their highest. The resulting stock market speculation constitutes a further drain on money capital.

In the course of the cycle, therefore, the interest rate must rise, even regardless of the devaluation of money. Money is always more expensive although the rate of profit is always falling. A point is reached where the profit realised in an enterprise is not even sufficient to fuel accumulation as required by technical necessity and competition. The possibilities of ‘self-financing’, as they say, are reduced, the capital of industry becomes, in increasing proportions, the property of the banks (imperialism); a greater part of the profit has to be converted into interest, for the money capitalist, the real industrial profit is thus reduced by two concomitant causes.

(A German bank bulletin states that from 1972 to 1975, the portion of funds that American industrial companies procured in the form of loans increased from 75% to 90%).

When the interest rate reaches and exceeds the profit rate the entrepreneurial enterprise works at a loss, it works solely for the bank. The figure of the capitalist (in the sense of the autonomous accumulation centre) becomes impossible, the salaried manager is needed. In effect, the bank-industry union takes shape, first in the distribution of surplus-value, then in the distribution of financial and material resources, and then in the distribution of products.

* * *

Interrupted in the previous issue, we are resuming the description of processes typical of industrial capital cycles. In this issue we have found space to publish the symbolic schema, whose description is partly in the last issue.

The transition from the phase of ‘productive expansion’ to that of recession and crisis is mediated, in the diagram, by the phenomenon ‘the size of the market grows slower than the scale of production’. The determinations of this phenomenon, the true damnation of capitalism, here can only be summarised in the contrasting effect of the increase in labour productivity added to the ever-expanding ‘proletarianisation’ on the one hand, and the fall in the rate of profit on the other.

Except in the moments following a crisis paralysing the productive apparatus, it is shown that even if there is still a demand for new means of production, the solvent demand for immediate means of consumption for society grows at a necessarily slower rate than the continuous swelling of constant capital. One need only open a statistical bulletin of any capitalist country and the verification leaps to the eye: the rate of increase in consumption is not equal to that of steel, for example. The reality is that ever-increasing masses of people scrape by at the exact limit of survival.

The lower part of the chart represents the crisis period. In it we recognise four distinct ‘vortices’, which is how we have tried to schematise the phenomena of this moment. First circuit, the monetary crisis. As the economy approaches the crisis, that portion of the product that accumulates unsold increases and at first only looms as a threat to price levels. The tightening of the market with the first signs of difficulties in the placement of goods and the news of the first non-payment of bills issued by private merchants causes payment difficulties in the sense that, due to the tightly interwoven network of credit relations, a delay in payment even in a few places spreads to the entire system, if only due to the waning confidence of creditors. If the phenomenon persists, soon the fiduciary credit issued by buyers is no longer accepted, ‘credit capital vanishes’, sellers demand payment at shorter notice or even in cash. Circulation at the moment demands money, insecurity about tomorrow erodes all trust in private credit; massive then is the recourse to more secured securities, banknotes and bank credit. This leads to a further decline in the percentage of ‘self-financing’, and an additional strong ‘interest rate hike’.

Marx is keen to make a clear distinction between this monetary demand and the previous demand for capital: as the crisis deepens, recourse to the banks is less and less motivated by the desire to expand accumulation for the future, more and more by the pressing need to pay for transactions that have already taken place, that have come to an end. This explains the simultaneous high interest rates and the so-called ‘plethora of capital’: when capital stops, money must run. In summary, we wrote ‘everybody wants to sell (merchants and ex-capitalists), nobody wants to buy’. In order to obtain liquid means of payment, industrialists and merchants are forced into ‘forced sales’ on pain of bankruptcy. Goods are put up for sale that the market does not demand (i.e. cannot pay for): this unnatural, untimely sale represents the sacrifice of the value of immense masses of commodities on the altar of money: in order to transform the values of commodities into money, any price is accepted, ‘only money is value’.

The credit crisis then converges in the ‘falling prin’. As of today, in 1977, this event has not occurred, but neither, as yet, has a full-blown credit collapse. On the international level, the time lags of recessions still allow for large transfers of gold and other means of payment that can postpone the failure of certain economies on the world market.

The cycle of the credit crisis therefore still cannot be closed through the ‘bankruptcies’ caused by deflation with the further protest of bills of exchange.

Connected to the credit crisis here appears the currency crisis. Its mechanism can be schematised as follows: the increase in international competition causes the weaker countries to run up a growing trade deficit; when the resulting obligations come due, whether the payments are settled immediately in gold or the metal is offered as collateral for new loans, the central banks’ treasuries must necessarily shrink. At the same time governments are driven, by the increasing demands on their means of payment and in order to curb the interest rate, to issue paper money without any correspondence to the value of their treasuries. This is the precondition for a currency devaluation as soon as the mass of means of circulation, necessary and actually demanded, by the market shrinks. After commodities have depreciated it is the turn of paper money to dissolve in the hands of the bourgeois, all its eternal idols have collapsed and only in the old yellow metal does it find refuge for its wealth. But to expect to convert all the signs of value in circulation and hoarded by society suddenly into gold is clearly impossible.

In the ‘financial’ sector of the chart, the main phenomenon of stock market crises is mentioned. The rise in the interest rate, together with a decline in the confidence of speculators, produces a tendency towards a ‘re-entry’ into the safer indirect investment of all the daredevils who in prosperous times had ventured into the stock market game. Selling prevails over buying and stock prices collapse. This, although very conspicuous in terms of the number of ‘small investors’ involved, has a non-immediate reflection on production since, at the moment of the crash, the capital represented by shares has already been paid in (at the time of their issuance) and put to work; what actually collapses are the hopes of the petty bourgeoisie for easy enrichment. It is, however, the big fish that are pulling the net at the moment, especially the big banks that rake in cheap industrial securities.

The whole manoeuvre reeks of catastrophe to the mass of investors, and by rushing to sell, they are merely throwing themselves into the arms of the financial monopoly.